Fixing the Next 10,000 Aliasing Bugs

Why do software bugs happen? There are many possible causes of bugs, but if we look at examples, we can hopefully see patterns in the bugs that arise and design our programming languages to rule out entire classes of bugs.

1) My first ArrayList

Suppose you’re back in freshman CS, studying data structures and algorithms, and you’re asked to implement an array-backed list in Java. You might write something like the following:

public class MyList<E> {

private E[] arr;

private int length;

public MyList() {

arr = (E[]) new Object[0];

length = 0;

}

public void ensureCapacity(int minCapacity) {

if (minCapacity > arr.length) {

int new_capacity = Math.max(minCapacity, arr.length * 2);

E[] new_arr = (E[]) new Object[new_capacity];

System.arraycopy(arr, 0, new_arr, 0, length);

arr = new_arr;

}

}

public boolean add(E e) {

ensureCapacity(length + 1);

arr[length++] = e;

return true;

}

public boolean addAll(MyList<? extends E> c) {

ensureCapacity(length + c.length);

for (int i = 0; i < c.length; i++) {

arr[length++] = c.arr[i];

}

return true;

}

}

This code is mostly correct, but has a subtle bug. The addAll method is intended to append all the elements of one list to another list. However, what if we pass a second pointer to the same list to addAll?

public static void main(String... args) {

MyList s = new MyList<Integer>();

s.add(42);

s.addAll(s); // boom!

}

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException: Index 2 out of bounds for length 2

at MyList.addAll(MyList.java:28)

at MyList.main(MyList.java:37)

Let’s look more closely at the implementation of addAll:

public boolean addAll(MyList<? extends E> c) {

ensureCapacity(length + c.length);

for (int i = 0; i < c.length; i++) {

arr[length++] = c.arr[i];

}

return true;

}

We first ensure that this has sufficient capacity to append the elements from c by calling ensureCapacity(length + c.length), and then append those elements one by one. The problem with this is that the code has an implicit invariant - that c.length does not change while we are appending the elements.

If c.length somehow increases while addAll is executing, then we may no longer have sufficient capacity to hold all the new elements despite reserving c.length worth of extra capacity at the beginning of the method. Since addAll itself does not change c.length, it might seem like it is impossible for this to happen (barring multi-threaded race conditions).

However, if c points to the same object as this, then every time we run length++ in the middle of the loop, c.length also increases because length and c.length point to the same field. This means that the for loop runs forever, repeatedly copying c onto the end of the list until we reach the edge of the backing array and crash with an ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException.

2) The DAO

Now let’s look at a famous real world bug. The DAO was a “smart contract” published to the Ethereum blockchain in 2016. The idea behind the DAO was to create a machine-operated investment fund that anyone could deposit and withdraw money from, with the operations governed purely by smart contract code running on the computers of “miners” on the Ethereum network.

Anyone could deposit money by calling a function in the smart contract, and they could later withdraw their money by calling another function*. The smart contract would internally keep track of how much each user is owed, and prevent users from withdrawing more money than they originally deposited, so that one person couldn’t just steal everyone else’s money.

* Technically speaking, you couldn’t withdraw money from the DAO directly. Instead, you had to split the DAO into two sub-contracts, one containing your money and one containing everyone else’s. Then you could take the money out of the new contract you created. However, the overall story is the same.

Unfortunately, one enterprising user noticed a bug in the contract that allowed them to bypass this check and withdraw “their money” multiple times without changing the contract’s internal balance, and thus they were able to drain all the money from the contract that everyone else had deposited (around $150 million). What went wrong?

Here is the relevant code from the DAO smart contract with comments added:

function splitDAO(

uint _proposalID,

address _newCurator

) noEther onlyTokenholders returns (bool _success) {

...

// XXXXX Move ether and assign new Tokens. Notice how this is done first!

uint fundsToBeMoved =

(balances[msg.sender] * p.splitData[0].splitBalance) /

p.splitData[0].totalSupply;

if (p.splitData[0].newDAO.createTokenProxy.value(fundsToBeMoved)(msg.sender) == false) // XXXXX This is the line the attacker wants to run more than once

throw;

...

// Burn DAO Tokens

Transfer(msg.sender, 0, balances[msg.sender]);

withdrawRewardFor(msg.sender); // be nice, and get his rewards

// XXXXX Notice the preceding line is critically before the next few

totalSupply -= balances[msg.sender]; // XXXXX AND THIS IS DONE LAST

balances[msg.sender] = 0; // XXXXX AND THIS IS DONE LAST TOO

paidOut[msg.sender] = 0;

return true;

}

Don’t worry about the details of the code. The important part is that this function sends money to the user before decreasing their internal balance. Just like our MyList example, this code has an implicit invariant.

The invariant is that every user’s balance matches up with the correct amount of money they are owed. When a user deposits money, two changes are required: you have to add the money to the contract and increase the user’s internal balance variable. And likewise when they withdraw money, you have to send them the money and decrease the user’s internal balance variable.

Since multiple steps are required, this means that the invariant is temporarily violated while the function is running. Once both steps are complete and the function returns, the invariant is restored. However, if there is some way to access the smart contract while the withdrawal function is still running, in between when it sends money to the user and when the internal balance variable is updated, the internal balance value will be incorrect and the user can withdraw they money a second time (and then a third and a fourth, until all the money is gone).

In the MyList example, the temporarily violated invariant was broken by having two aliased pointers pointing to the same object. In the DAO case, the aliasing involved is more subtle.

As it turns out, Solidity (the language that Ethereum smart contracts were written in) allows you to define a fallback function when money is sent to a contract, and this function can execute arbitrary code. Therefore, the attacker just created a smart contract with a fallback function that attempts to withdraw money from the DAO again, and then asked the DAO to withdraw money into their smart contract. When the DAO sent money to the attacker, this triggered the fallback function, which called the DAO withdraw function again while the original withdraw function was still running and the balance value was not yet updated allowing them to endlessly withdraw money.

Here, the fatal aliasing wasn’t due to multiple variables pointing to the same object, but rather copies of the same variable in multiple stack frames, as the same function was called reentrantly.

3) Uber

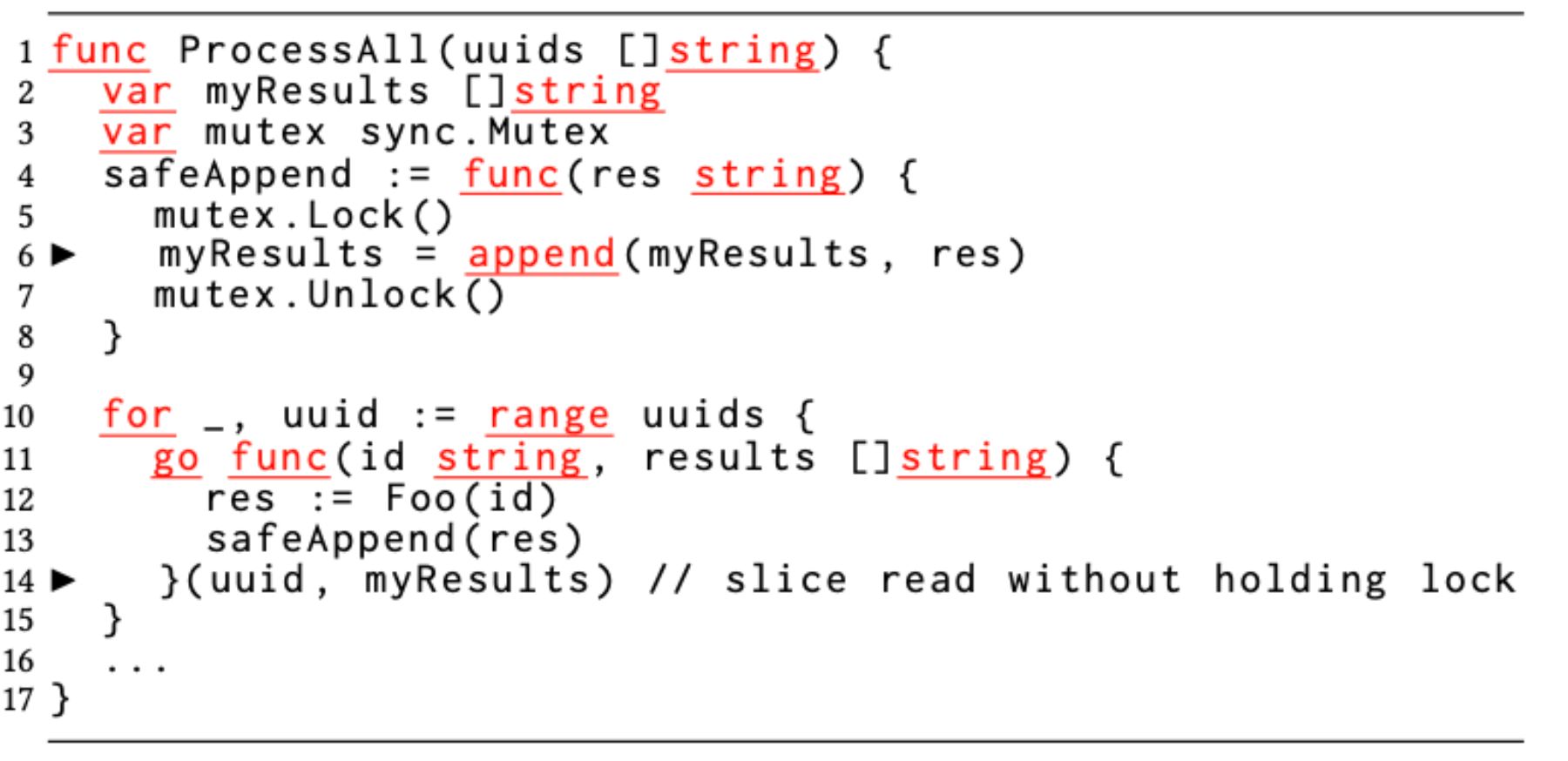

Last year, Uber published a blog post detailing the most common types of bugs they’ve seen in their production Go code. The most common bug pattern they saw was concurrent slice access, as in the following example.

In Go, slices are basically like an un-encapsulated version of our MyList class in the first example. They consist of a (data pointer, length, capacity) tuple. When you assign or pass around a slice value, those fields are all copied by value. The length and capacity are copied by value, and the data pointer is also copied by value, which is equivalent to passing the data array by reference. This makes it easy to end up with multiple slice values that share the same data array but have inconsistent length and capacity values.

In Uber’s example, the programmer realized that they needed something to protect against race conditions and added a mutex to the safeAppend function. However, this merely prevents multiple threads from running safeAppend simultaneously, and thus writing to myResults simultaneously. The read of myResults on line 14 is not protected by the mutex at all.

This means that the read of myResults (which is passed to results on line 11) may happen while myResults is simultaneously being written to on line 6. That means that the read may see garbage data, such as if myResult’s capacity field is updated before the data pointer field, and thus results copies a capacity value that does not match its data pointer. Uber’s example does not show results being used anywhere, but if it was used, this might result in out-of-bounds memory access, and thus arbitrary code execution and critical security vulnerabilities.

The Go runtime has an invariant that the three fields of a slice value are consistent, and this invariant is violated via concurrent access to multiple references to myResults, specifically a mutable access to myResults in one of the spawned go routines concurrently with a read access to myResults from the main thread.

However, even if the Go runtime’s invariant was protected by putting a mutex around the read of myResults on line 14, this code likely still violates logical invariants. Namely, the programmer presumably assumes that the results values will hold a consistent state that matches myResults. However, since results is just copied from myResults at an arbitrary point, they will likely end up with inconsistent data. If the goroutine then attempts to access results, this could lead to the result values being overwritten, or failing to see results values that were previously appended.

Invariants and aliasing

What do all three of these bugs have in common? In every case, an invariant was violated thanks to multiple aliased references to the same value.

Invariants are essential to large scale programming, because it is impossible to hold the entire state of a system in your head at once. Invariants allow you to focus only on the parts of the code responsible for upholding that invariant, and to just assume it holds elsewhere, thus reducing the combinatorial explosion of the state space and allowing the development of software larger than trivial toy examples.

However, code inevitably needs to temporarily violate an invariant while performing updates. The problem comes when there are multiple references to the relevant data, and another reference observes this temporarily violated invariant.

Preventing aliasing bugs

Now that we’ve recognized the problem, the next question is how to prevent these bugs.

As it turns out, we’ve been here before. The null pointer has been described as “the billion dollar mistake” due to the sheer number of bugs that resulted from null pointers. For decades, programmers just shrugged and accepted NullPointerExceptions (or seg faults or undefined is not a functions, depending on your poison of choice) as a fact of life. You just have to try harder to make sure you don’t slip up, right?

However, more recently, programmers realized that things didn’t have to be this way, and a new generation of programming languages came out where nullability is encoded in the type system. Instead of every value possibly being null, only the values explicitly so marked by the programmer might be null. For the remainder, the compiler would statically verify that they are never null, vastly reducing the surface of potential null pointer bugs. Humans will always slip up from time to time, which is why it is important to develop systems that will catch and prevent these mistakes.

The time has come to do the same for aliasing bugs, to banish them at the programming language level once and for all.

Alias typing

What might such a language look like?

In the case of null pointers, every reference in a traditional language is implicitly nullable, while in a modern language, you can mark references as nullable or non-nullable, and the latter are statically guaranteed to be non-null. Likewise, in a traditional language, every reference is implicitly aliasable. Therefore, by analogy, in our language, all references will be marked as shared or exclusive and an exclusive reference is statically guaranteed to be non-aliased.

For the sake of example, I’ll write these as shr and xcl respectively, e.g. xcl List or shr Map, but you’ll probably want to use different syntax in your language. The point of this post is to illustrate how type checking can be used to rule out most aliasing bugs, not to dictate surface-level syntax.

What rules do these types need? First off, when a new object is created, the resulting reference is guaranteed unique, so all objects start out xcl. Furthermore, you can always implicitly convert an exclusive reference to a shared reference, but not the reverse, much like how a non-nullable reference can be implicitly converted to a nullable reference, but not the reverse.

Non-copyable types

The last rule we need is a bit different: exclusive references can’t be copied. (You can of course convert an exclusive reference to a shared reference and then copy it as much as you want.) This means that when you use an exclusive reference, it is moved rather than copied. The compiler needs to ensure that the old variable is no longer accessed. E.g.

let foo: xcl Foo = new Foo;

let bar = foo; // foo is moved to bar

foo; // compile error - foo can't be accessed any more

Permissions and invariant removal

In the case of nullable pointers, the input type required is obvious. If a piece of code accesses a reference without checking it for null, then it needs to take in a non-nullable reference. If it does check for null explicitly, then it is safe to take in a nullable reference instead. What is the equivalent for alias typing? When do you actually need an exclusive reference, and when can you get away with using shared references?

The answer is that an exclusive reference is required to remove invariants. If you want to violate an invariant, even temporarily, you need to ensure that no other reference can possibly observe the violated invariant, and thus you need an exclusive reference. If your code does not require removing any invariants from a value, you can safely use shared references.

For example, imagine that we have an UInt type for (mutable) unsigned integer objects and a NonZero type that represents UInts with the additional invariant of holding a nonzero value. We might write a function that takes in a nonzero int and temporarily violates the invariant like this:

fn increment(x: xcl NonZero) -> xcl NonZero {

let x = x as UInt; // remove invariant

*x += 1;

// check for overflow and ensure value is nonzero

if *x == 0 {

*x = 0xFFFFFFFF; // saturate at max value

}

// add the invariant back

return x as NonZero;

}

Personally, I like to think of xcl and shr as permissions for the associated references. However, these aren’t quite the same as permissions like “can read” or “can write” that you’re probably used to thinking of as “permissions”. Rather, xcl is the permission to assume that noone else is accessing this value, which in turn implies the permission to remove invariants.

You can of course create an arbitrarily fine-grained permission system if you want to. For instance, you might have one permission type for pointers where only you can write to the pointer but other copies may exist that can read the value. But the two permission xcl/shr system illustrates all the fundamental design considerations required, so I’ll stick with it for simplicity.

Time-limited permissions

The above system is straightforward to implement, but it isn’t very useful. The problem is that you can only ever use an exclusive reference once, which makes it impossible to do anything interesting. You can partially work around this by always returning the new value and assigning it back at the callsite, but this quickly becomes cumbersome.

Suppose for example, that we want to call our increment function twice. We would have to do something like this:

fn increment_twice(x: xcl NonZero) -> xcl NonZero {

let x = increment(x);

let x = increment(x);

return x;

}

But what if we want to add loops or conditionals? What if we’re operating on a bunch of different values? What if we are mapping over a list of values? The “return value and reassign at callsite” style is very limited, in addition to being verbose. It would be a lot more convenient if we could do the operations by reference instead.

We would like to be able to do something like this.

fn increment(x: xcl NonZero) {

// ...

}

fn increment_twice(x: xcl NonZero) {

increment(x);

increment(x); // ???

}

However, the increment_twice function doesn’t work because x was already moved on the first call to increment. Intuitively, this code should work though. After all, increment only needs temporary exclusive access to x. Once the call to increment completes, it doesn’t hold on to any references to x, so we should be able to treat x as exclusive again in the parent increment_twice function, and thus be able to call increment a second time.

The solution is time-limited permissions. Instead of granting increment permanent exclusive access to x, we only grant it temporary exclusive access to x for the duration of the call, and thus can call it again after the first call completes.

Permission grants

So how do we implement this? And in particular, how can we do the type checking without costly inter-procedural code analysis? How can we represent all the information required to check time-limited permissions in just the type annotations?

In addition to a permission (xcl or shr), each reference type optionally has a grant parameter, which tracks temporary permission grants and when they can be revoked. In the example syntax, I will write grants using a leading apostrophe, i.e. 'a xcl Foo. Note that these exist purely at compile time. The permission types are merely for static type checking to prevent bugs. At runtime, everything is compiled down to ordinary pointers, and there is no runtime overhead.

Additionally, I’ll introduce the 'call keyword to represent the duration of the current function call. Therefore, we can write increment as follows:

fn increment(x: 'call xcl NonZero) {

// ...

}

Note that grant parameters will always be generic, because every instance of every call will have a different grant. So 'call here is really shorthand for “any 'a such that 'a lasts at least as long as 'call”. For the sake of example syntax, we’ll write this as

fn increment<'a: 'call>(x: 'a xcl NonZero) {

// ...

}

This explicit syntax allows us to also express dependencies between arguments and return values. For example, suppose we modify increment to return the input again, like before. We could write this type signature as

fn increment<'a: 'call>(x: 'a xcl NonZero) -> 'a xcl NonZero {

// ...

return x as NonZero;

}

Since the argument and return value have the same grant parameter, the compiler can know that the return value depends on the input without looking at the body of the function.

Now let’s get back to increment_twice and make it a bit more interesting, by storing the return value and adding some extra increment calls, attempting to increment four times in total, but using a stale reference for the last call which should result in a compile error:

fn increment_four_times<'b: 'call>(x: 'b xcl NonZero) {

let y = increment(x);

increment(y); // ok

increment(x); // also ok

increment(y); // compile error - y's permission grant has been revoked by this point

}

Permission splitting

To typecheck this code, we’ll need to introduce the notion of splitting permissions, which is the most counter-intuitive part of alias checking.

We already got a taste of this with the initial version of non-copyable types above:

let a: xcl Foo = new Foo;

let b = a;

// b has type xcl Foo, a has type undefined

Essentially, a has a certain amount of permissions to access its content. In the simple case with non-copyable types, we transfer the entire permission to the new value whenever we read a variable. This means that the original variable a no longer has any permissions and thus can’t be accessed.

However, instead of transfering a’s permissions permanently when read, we can instead only transfer part of the permissions, specifically, the part that allows access before a given point in time. Then b can only be accessed before that time and a can only be accessed after that point in time, and thus there is no conflict in them both having a (time-limited) exclusive permission attached.

More specifically, when we read a, we’ll give the read value (b) the type '0 xcl Foo, where '0 is a freshly generated grant variable, representing that b can be accessed until the grant '0 is revoked. Meanwhile, a will have the type “can be accessed as xcl Foo by first revoking the '0 grant”. We’ll write 'n -* T to represent the type “can revoke 'n to access as T”, so a has the type '0 -* xcl Foo. Note that -* is just example syntax for the sake of discussion. In practice, these types will only be used for internal bookkeeping by the compiler and never be exposed to the user, so it doesn’t matter if the syntax is ungainly.

Type-checking example

With that machinery out of the way, we can see an example of how our fancy increment_twice function will be typechecked. Recall that the code is as follows:

fn increment_four_times<'b: 'call>(x: 'b xcl NonZero) {

let y = increment(x);

increment(y); // ok

increment(x); // also ok

increment(y); // compile error - y's permission grant has been revoked by this point

}

We start with all variables (i.e. just x) having the types from the function signature:

fn increment_four_times<'b: 'call>(x: 'b xcl NonZero) {

// types: x: 'b xcl NonZero

let y = increment(x);

increment(y); // ok

increment(x); // also ok

increment(y); // compile error - y's permission grant has been revoked by this point

}

Now we get to the x in the first increment(x). We generate a fresh grant variable, '0, and assign the type '0 xcl NonZero to the temporary value read from x. Meanwhile, the local variable x has its type changed to '0 -* 'b xcl NonZero. This means that it currently has no permissions, but will regain the 'b xcl NonZero permission by revoking the '0 grant.

Next, we match the argument value against the type signature of increment, and thus 'a matches with '0. Thus we know that the return value has the same grant, so y gets the type '0 xcl NonZero.

fn increment_four_times<'b: 'call>(x: 'b xcl NonZero) {

let y = increment(x);

// types: x: '0 -* 'b xcl NonZero, y: '0 xcl NonZero

increment(y); // ok

increment(x); // also ok

increment(y); // compile error - y's permission grant has been revoked by this point

}

Next we do the same thing with the increment(y) line, generating a '1 sub-grant variable. This doesn’t matter because we aren’t storing the return value this time, and thus can revoke the grant any time we want, but I’m listing it explicitly for the sake of clarity.

fn increment_four_times<'b: 'call>(x: 'b xcl NonZero) {

let y = increment(x);

increment(y); // ok

// types: x: '0 -* 'b xcl NonZero, y: '1 -* '0 xcl NonZero

increment(x); // also ok

increment(y); // compile error - y's permission grant has been revoked by this point

}

The interesting part happens when we get to the second increment(x) call. increment requires an argument of type 'a xcl NonZero for some 'a, but our x variable currently has the type '0 -* 'b xcl NonZero. Therefore we revoke the '0 grant, which changes the type back to 'b xcl NonZero'. Since '1 depends on '0, it gets revoked as well. y is no longer accessible at all.

After changing the type of x back to 'b xcl NonZero', we can then split it like before, resulting in a new local grant variable, so we generate a temporary value with type '2 xcl NonZero to pass to increment and change the type of the x variable to '2 -* 'b xcl NonZero.

fn increment_four_times<'b: 'call>(x: 'b xcl NonZero) {

let y = increment(x);

increment(y); // ok

increment(x); // also ok

// types: x: '2 -* 'b xcl NonZero, y: undefined

increment(y); // compile error - y's permission grant has been revoked by this point

}

Lastly, we get to the final line, where we try to read from y again. However, by this point, y’s grant has been revoked, and thus it can’t be accessed anymore, so we return a compile error.

First class -* types

Note that in this design, the only time we ever use -* types is for local variables during type checking. Whenever a local variable is read, we revoke grants in front of the -* if applicable and then re-split off as a normal type. Therefore, the user will never see or deal with -* types, they’re just a mechanism to describe the internals of type checking.

Furthermore, all grant variables are local to the function being typechecked, and only fresh grants defined in the same function ('0, '1, etc. as opposed to 'b) can appear in front of the -*. This ensures that we can statically revoke the grants during typechecking, and therefore can erase them during compilation, and there is no runtime overhead.

This system should be good enough for ordinary code, but there are rare cases where you might want to give the users more control over typechecking, and allow them to define custom -* types and pass them around. For example, they are useful for representing mutex guards and coroutines. However, these uses should be rare and will usually be hidden inside a standard library, so the complexity there shouldn’t be an issue in practice.

Type inference

Obviously this makes types more verbose, but judicious use of type inference or type defaulting can greatly reduce the burden of explicit permission types. I think that it still makes sense to require explicit xcl/shr in function signatures, since those are useful for documentation purposes and not much different from the const T annotations that you already see in existing languages.

However, the grant variables are a bit ugly and a pain to manage. Therefore, type inference should be used to remove the need to explicitly write them as much as possible. As far as I know, there is no decidable way to fully infer them, and you probably don’t want to do that anyway for efficiency and error-message quality reasons. However, you can still infer them in simple cases, i.e. private non-recursive functions.

The elephant crab

And now for the elephant crab in the room: the system I’ve described is similar to that of the existing programming language Rust and its “borrow checker”.

People often think that Rust is hard to learn due to its borrow checker and think “well, maybe you need a borrow checker if you want to write C++ correctly, but why do we need it for a Java/Python/Javascript competitor?” Why can’t we just use a GC and throw off the dread borrow checker?

This logic however, is precisely backwards. It is true that Rust is designed to replace C++, and that Rust has a borrow checker, and that the borrow checker is necessary in order to safely perform the kind of memory management people are used to in C++. However, that doesn’t mean that the borrow checker is only useful or necessary when doing C++, or that it isn’t useful in a GC’ed language. Memory management is the least interesting application of borrow checking.

One of the goals of writing this post is to show how the logic of preventing common bugs inexorably leads to something that is at least vaguely similar to Rust’s borrow checker (of course it doesn’t have to be identical - there’s still lots of room for improvement over Rust here!). In fact, two of the three languages from the bug examples section have garbage collectors. Far from removing the need for a borrow checker, GC merely removes some of the hassle of using a borrow checker.

Conclusion

In this post, we saw a very common class of bugs, those caused by aliasing, and how to statically prevent these bugs via typechecking. Although alias types are a bit more exotic than traditional type systems (in particular, types are only temporarily valid), they aren’t that hard to get used to and are important for preventing bugs.

Null checking was once unusual as well, but now, in this age of Kotlin and strictNullChecks TypeScript, nobody will take a language without null checking seriously. I think that someday, the same will be true of alias checking as well.