Solving the Traveling Pacman Problem

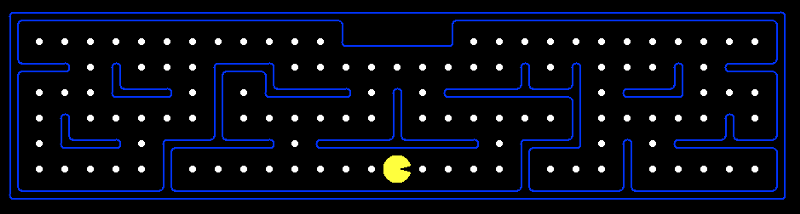

When I was in college, one class assignment gave us a set of Pacman mazes and asked us to write an A* search heuristic that would find the shortest path which visits every food pellet at least once. This is obviously similar to the famously NP-Hard Traveling Salesman Problem, but the mazes we were required to solve were small enough that even an exponential solution would work. However, there was also a much larger maze included which the assignment instructions said was impossible to solve, and if our code did terminate in a reasonable amount of time on it, it meant there was a bug in our code. Naturally, I couldn’t turn down a challenge like that, and this is the story of how I solved it.

A* Search

The assignment provided the game engine and A* implementation, with the only part of the code that we were supposed to change being the heuristic function. There are several obvious heuristics one could use for this problem, such as the number of uneaten food, or the maximum distance to a food, or even the length of the minimum spanning tree of the food. But this is a trap. To see why, consider how A* search is supposed to work.

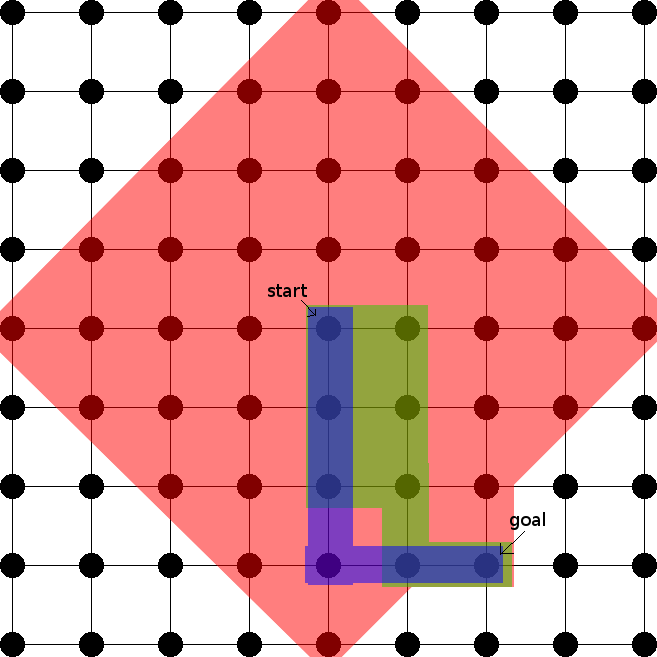

The most classic application of A* search is to 2d pathfinding, as depicted below. The red, green, and blue nodes show the nodes expanded during search when using the null heuristic, euclidean distance (a good but not perfect heuristic) and manhattan distance (a perfect heuristic in this case) respectively. The null heuristic expands every single node within distance 4 of the origin, while the euclidean heuristic only expands a few extra nodes and the manhattan heuristic goes straight to the goal without expanding any extra nodes.

Illustration of 2d A* search with various heuristics

Obviously, the better the heuristic, the fewer nodes are expanded. However, even with the null heuristic, where A* devolves into a simple breadth first search, only quadratically many nodes are expanded. This is because in a sense, the search space is quadratically big. For any given node, there are at most O(k²) nodes that are k steps away. This means that if your heuristic differs from the optimal heuristic by k, the search will expand at most O(nk²) incorrect nodes.

For the Pacman problem by contrast, the search space is exponentially large. Even though the maze itself is small, each possible subset of eaten food represents a different state in the search space. Unlike with the pathfinding example, moving up and then left will not result in the same state as moving left and then up, because a different set of food will have been eaten.

This means that there are up to O(3ᵏ) nodes that are k steps away from any given node, and any heuristic that is short of perfection is likely to lead to an exponential search complexity. This makes A* search unsuitable for the problem, no matter how clever you try to be with the heuristic function.

However, there is one out: a perfect heuristic function. The optimal solution is only linearly long (in fact, it will visit every edge at most twice), so if the A* search never takes a single wrong step, then the overall search time will be linear as well (ignoring the complexity of the heuristic function itself).

Note: There could be exponentially many optimal paths of the same length, but this is easily solved by making the A* search break ties in favor of the longest path.

This of course leads to the question of how to find an efficient perfect heuristic function. However we are now at least freed from the confines of A*: We can use any algorithm we want to calculate the length of the optimal path and then feed the results back to the A* search as a “heuristic”.

The exponential algorithm

The mazes required to be solved for the assignment were all sparse — most of the maze was empty, with only a handful of food pellets, meaning we can speed things up by only considering the food. Instead of trying to find the shortest path in a large maze of n nodes, where we only care about m of them (the number of food), we can instead pretend to solve a problem in a maze of m nodes.

One of the homework mazes: note all the empty spaces.

To do this, just precompute the shortest distance between every pair of food, and find the shortest path in the complete graph Kₘ where the edge weights are equal to said distances. Note that you also have to add the distance from Pacman’s current location to the food in addition to the distances between the food themselves, but this is easily done with standard distance finding algorithms.

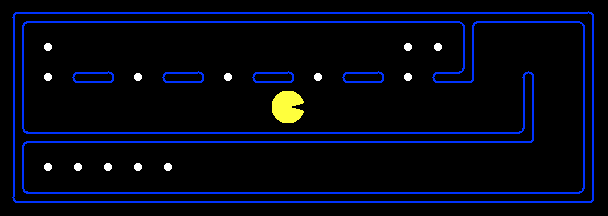

The naive brute force approach is O(m!), but this can be reduced to O(m²2ᵐ) using simple dynamic programming (memoize on the subset of uneaten food and the starting food). For the homework mazes, m was small enough that this was sufficient. However, the “impossible” maze was much larger, and every square had food in it. In order to solve it, I would need a more sophisticated approach.

Biconnected components

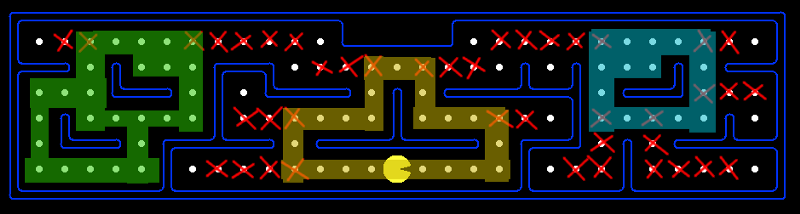

I was of course not foolish enough to think that I could prove P=NP. The reason I was confident I could solve it is because the mazes weren’t just arbitrary graphs. In fact, they were poorly connected. If you look closely at the maze below, you’ll notice that there are many points where removing a single square cuts the maze in two.

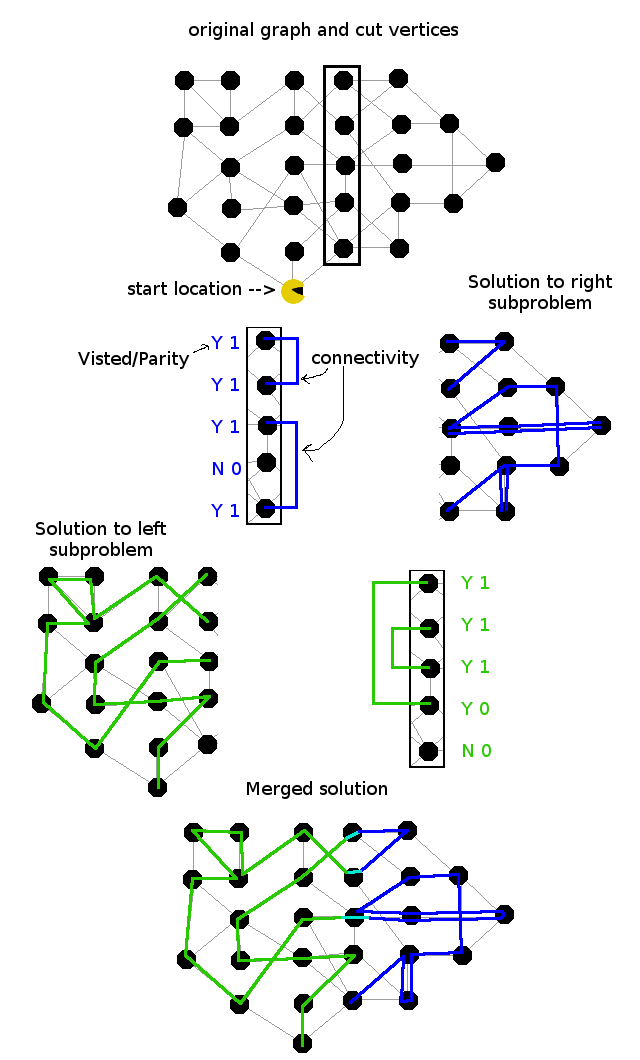

mediumSearch with cut nodes and large biconnected components marked

This makes solving much easier, because such a cut vertex, is the “interface” between the components. Each component doesn’t care at all what happens in the other. If you have an optimal path that visits every food in the left component, and an optimal path that visits every food in the right component, you can join them together into a solution for the entire maze.

The only information required to ensure they can be joined is to make sure the parity of the number of edges going out of the cut vertex matches up. So in order to find a solution to the entire maze, you can find the optimal odd and even solutions to the left component, and independently find the optimal odd and even solutions to the right component, and then join them together and pick the best result.

This effectively reduces the complexity of solving the maze to be exponential in the size of the largest biconnected component. Unfortunately for the mediumSearch maze, the largest component (highlighted in green above) had 26 nodes, which was still too large to be solved, or at least solved quickly in Python on an old laptop. Therefore, I needed to find further improvements.

Carving decomposition

The next step was to consider cuts of 2 vertices in addition to cuts of a single vertex. The biconnected components all have large “tunnels”, so a 2-cut would be sufficient to reduce them to a manageable size. However, it is much more complicated than the single vertex case because you have to consider the connectivity as well.

After some research, I came across the notion of a carving decomposition, and its use in fixed parameter tractable algorithms for similar problems. The trick is to generalize not just to cuts of 2 vertices, but to arbitrary numbers of vertices.

In the case of multiple vertex cuts, there are several complications that don’t apply in the single vertex case. First off, you have to keep track of which set of vertices in the cut each sub-solution visits. In the single vertex case, both sub-solutions must visit the vertex, but in the multiple vertex case, it is ok to visit only a subset, as long as every vertex in the cut is visited from at least one side, and there is at least one vertex of overlap so the sub-solutions can be joined together.

Additionally you have to keep track of which cut vertices are connected by each sub-solution. This is necessary to ensure that the sub-solutions can be joined together into a single path, rather than a bunch of disconnected loops. An illustration of such joining is shown below. Note that this “solution” is not optimal, it was just chosen to depict the process.

Diagram showing path merging

Given any specific tuple of (visited nodes, connectivity, parity), the rest of the sub-solution is irrelevant to determining whether it can be joined into a larger solution, so the usual dynamic programming techniques still apply.

The idea behind a carving decomposition is to split the entire graph up with such cuts, leaving only single nodes as the base case for the recursion. The size of the largest cut required is known as the carving width of the graph, and it is this which determines the complexity of the overall algorithm.

Since for each cut, the number of (visited nodes, connectivity, parity) cases to consider is exponential in the number of vertices in the cut, the algorithm is exponential in the carving width of the graph. However, if you hold width constant, the algorithm is otherwise polynomial in the size of the graph, making it what is known as a fixed parameter tractable algorithm.

As an aside, carving width is unbounded, even for planar grid graphs. For example, an n x n grid has a carving width of n, since there is no way to split the graph completely without cutting at least one vertex from every row or column. In this case, the fixed parameter tractable algorithm would have exponential complexity. Luckily, we are dealing with poorly connected graphs, rather than giant grids.

The last question is how to actually find the carving decomposition. There are algorithms to find an optimal carving decomposition of planar graphs in polynomial time, but I found them too difficult to understand and implement, so I decided to just use the greedy algorithm to find a non-optimal decomposition, which worked well enough for the mazes in question. Once all this was implemented and optimized, my code was able to solve mediumSearch in under 5 seconds on my laptop, thus conquering the impossible challenge.

bigSearch

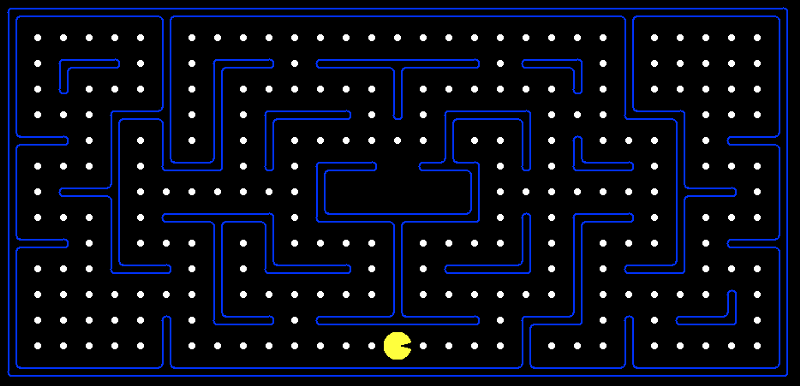

In addition to mediumSearch, the assignment also comes with a much larger maze known as bigSearch. Although our class did not use it, many versions of this assignment at other colleges include a contest where students compete to find the best (non-optimal) solution in under 30 seconds. This maze can be solved optimally using the same algorithm as before, although the higher carving width means it takes longer. Since my final code can solve this optimally in under 30 seconds, I like to think I won those contests in spirit.

The big maze