How ES6 classes really work and how to build your own

The 6th edition of ECMAScript (or ES6 for short) revolutionized the language, adding many new features, including classes and class based inheritance. The new syntax is easy to use without understanding the details and mostly does what you’d expect, but if you’re like me, that isn’t quite satisfying. How does the seemingly magical syntax actually work under the hood? How does it interact with other features in the language? Is it possible to emulate classes without using the class syntax? Here, I will answer these questions in gratuitous detail.

But first, in order to understand classes, you must understand what came before them, and Javascript’s underlying object model.

Object model

The Javascript object model is fairly simple. Each object is just a mapping of strings and symbols to property descriptors. Each property descriptor in turn holds either a getter/setter pair for computed properties or a data value for ordinary data properties.

When you execute the code foo[bar] , it converts bar to a string if it isn’t already a string or symbol, then looks up that key among foo’s properties and returns the value of the corresponding property (or calls its getter function as applicable). For literal string keys that are valid identifiers, there is the shorthand syntax foo.bar which is equivalent to foo["bar"]. So far, so simple.

Prototypal inheritance

Javascript has what is called prototypal inheritance, which sounds scary, but is actually simpler than traditional class based inheritance once you get the hang of it. Each object may have an implicit pointer to another object, referred to as its prototype. When you try to access a property on an object where no property exists with that key, it instead looks up the key on the prototype object, and returns the prototype’s property for that key if it exists. If it doesn’t exist on the prototype, it recursively checks the prototype’s prototype and so on, all the way up the chain until a property is found or an object without a prototype is reached.

If you have used Python before, the attribute lookup process is similar. In Python, each attribute is first looked up in the instance dictionary. If it is not present there, the runtime then checks the class dictionary, then the super class dictionary, and so on, all the way up the inheritance hierarchy. In Javascript, the process is similar except that there is no distinction between type objects and instance objects — any object can be the prototype of any other object. Of course, in the real world, people rarely use this fact and instead organize their code into class-like hierarchies, because it is easier to manage that way, which is why Javascript added class syntax in the first place.

Internal slots

If all an object consists of is a mapping of keys to properties, where is the prototype stored? The answer is that in addition to properties, objects also have internal methods and internal slots, which are used to implement special language level semantics. Internal slots cannot be directly accessed from Javascript code in any way, but in some cases, there are ways to indirectly access them. For example, object prototypes are represented by the [[Prototype]] slot which can be read and written using Object.getPrototypeOf() and Object.setPrototypeOf() respectively. By convention, internal slots and methods are written in [[double square brackets]] to distinguish them from ordinary properties.

Old style classes

In early versions of Javascript, it was common to simulate classes using code like the following.

function Foo(x) {

this.x = x;

this.y = 432;

}

Foo.prototype.point = function() {

return 'Foo(' + this.x + ', ' + this.y + ')';

}

var myfoo = new Foo(99);

console.log(myfoo.point()); // prints "Foo(99, 432)"

Where did this come from? Where did prototype come from? What does new do? As it turns out, even the earliest versions of Javascript didn’t want to be too unconventional, so they included some syntax that let you code things that were kinda-sorta like classes.

In technical terms, functions in Javascript are defined by the two internal methods [[Call]] and [[Construct]] . Any object with a [[Call]] method is called a function, and any function that additionally has a [[Construct]] method is called a constructor¹. The [[Call]] method determines what happens when you invoke an object as a function, e.g. foo(args) , while [[Construct]] determines what happens when you invoke it as a new expression, i.e. new foo or new foo(args) .

For ordinary function definitions², calling [[Construct]] will implicitly create a new object whose [[Prototype]] is the prototype property of the constructor function if that property exists and is object valued, or Object.prototype otherwise. The newly created object is bound to the this value inside the function’s local environment. If the function returns an object, the new expression will evaluate to that object, otherwise, the new expression evaluates to the implicitly created this value.

As for the prototype property, that is implicitly created whenever you define an ordinary function. Each newly defined function has a property named “prototype” defined upon it with a newly created object as its value. That object in turn has a constructor property which points back to the original function. Note that this prototype property is not the same as the [[Prototype]] slot. In the previous code example, Foo is still just a function, so its [[Prototype]] is the predefined object Function.prototype .

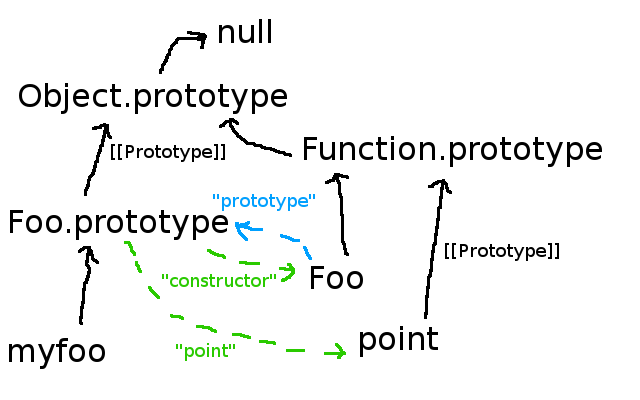

Here is a diagram to illustrate the previous code sample with [[Prototype]] relationships in black and property relationships in green and blue.

Diagram of prototype hierarchy for previous code sample

[1] You could conceivably have objects with a [[Construct]] method and no [[Call]] method, but the ECMAScript specification does not define any such objects. Therefore, all constructors are also functions.

[2] By ordinary function definitions, I mean functions defined using the regular function keyword and nothing else, rather than => functions, generator functions, async functions, methods, etc. Of course, prior to ES6, this was the only kind of function definition.

New style classes

With that background out of the way, it’s time to examine ES6 class syntax. The previous code sample translates directly to the new syntax as follows:

class Foo {

constructor(x) {

this.x = x;

this.y = 432;

}

point() {

return 'Foo(' + this.x + ', ' + this.y + ')';

}

}

let myfoo = new Foo(99);

console.log(myfoo.point()); // prints "Foo(99, 432)"

As before, each class consists of a constructor function and a prototype object which refer to each other via the prototype and constructor properties. However, the order of definition of the two is reversed. With an old style class, you define the constructor function, and the prototype object is created for you. With a new style class, the body of the class definition becomes the contents of the prototype object (except for static methods), and among them, you define a constructor. The end result is the same either way.

So if the ES6 class syntax is just sugar for old style “classes”, what’s the point? Apart from looking a lot nicer and adding safety checks, the new class syntax also has functionality that was impossible pre-ES6, specifically, class based inheritance. When you define a class with the new syntax, you can optionally provide a super class for the class to inherit from as demonstrated below:

class Base {

foo() {return 'foo in Base';}

bar() {return 'bar in Base';}

}

class Child extends Base {

foo() {return 'foo in Child';}

whiz() {return 'whiz in Child';}

}

const b = new Base;

const c = new Child;

console.log(b.foo()); // foo in Base

console.log(b.bar()); // bar in Base

console.log(c.foo()); // foo in Child

console.log(c.bar()); // bar in Base

console.log(c.whiz()); // whiz in Child

This example by itself can still be emulated without class syntax, although the code required is a lot uglier.

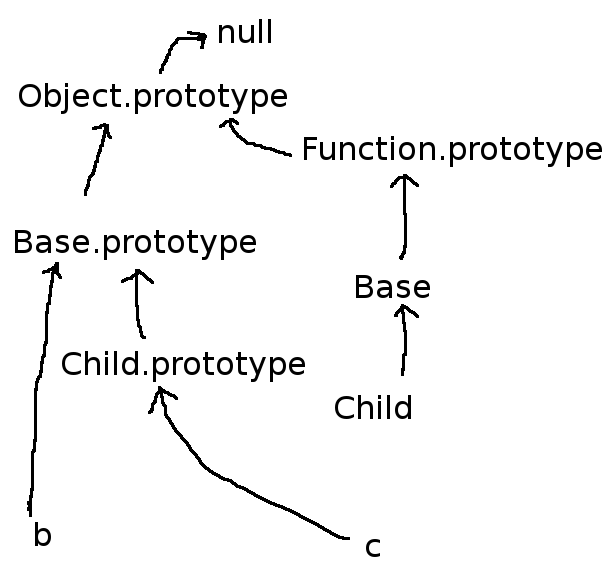

With class based inheritance, the rule is simple — each part of the pair has as its prototype the corresponding part of the superclass. So the constructor of the superclass is the [[Prototype]] of the subclass constructor and the prototype object of the superclass is the [[Prototype]] of the subclass prototype object. Here’s a diagram to illustrate (only the [[Prototypes]] are shown; properties are omitted for clarity).

There is no direct and convenient way to set up these [[Prototype]] relationships without using class syntax, but you can set them manually using Object.setPrototypeOf(), introduced in ES5.

function Base() {}

Base.prototype.foo = function() {return 'foo in Base';};

Base.prototype.bar = function() {return 'bar in Base';};

function Child() {}

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child, Base);

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child.prototype, Base.prototype);

Child.prototype.foo = function() {return 'foo in Child';};

Child.prototype.whiz = function() {return 'whiz in Child';};

var b = new Base;

var c = new Child;

console.log(b.foo()); // foo in Base

console.log(b.bar()); // bar in Base

console.log(c.foo()); // foo in Child

console.log(c.bar()); // bar in Base

console.log(c.whiz()); // whiz in Child

However, the example above notably avoids doing anything in the constructors. In particular, it avoids super, a new piece of syntax that allows subclasses to access the properties and constructor of the superclass. This is much more complicated, and is in fact impossible to fully emulate in ES5, although it can be emulated in ES6 without using class syntax or super through use of Reflect.

Superclass property access

There are two uses for super — calling a superclass constructor, or accessing properties of the superclass. The second case is simpler, so we’ll cover it first.

The way that super works is that each function has an internal slot called [[HomeObject]] , which holds the object that the function was originally defined within if it was originally defined as a method. For a class definition, this object will be the prototype object of the class, i.e. Foo.prototype. When you access a property via super.foo or super[“foo”], it is equivalent to [[HomeObject]].[[Prototype]].foo.

With this understanding of how super works behind the scenes, you can predict how it will behave even under complicated and unusual circumstances. For example, a function’s [[HomeObject]] is fixed at definition time and will not change even if you later assign the function to other objects as shown below.

class A {

foo() {return 'foo in A';}

}

class B extends A {

foo() {return 'foo in B';}

}

class C {

foo() {return 'foo in C';}

}

class D extends C {

foo() {return super.foo();}

}

b = new B;

console.log(b.foo()); // foo in B

B.prototype.foo = D.prototype.foo

console.log(b.foo()); // foo in C

console.log(b instanceof C); // false

In the above example, we took a function originally defined in D.prototype and copied it over to B.prototype. Since the [[HomeObject]] still points to D.prototype, the super access looks in the [[Prototype]] of D.prototype, which is C.prototype. The result is that C’s copy of foo is called even though C is nowhere in b’s prototype chain.

Likewise, the fact that [[HomeObject]].[[Prototype]] is looked up on every evaluation of the super expression means that it will see changes to the [[Prototype]] and return new results, as shown below.

class A {

foo() {return 'foo in A';}

}

class B {

foo() {return 'foo in B';}

}

class C extends A {

foo() {

console.log(super.foo()); // foo in A

Object.setPrototypeOf(C.prototype, B.prototype);

console.log(super.foo()); // foo in B

}

}

c = new C;

c.foo();

As a side note, super is not limited to class definitions. It can also be used from any function defined within an object literal using the new method shorthand syntax, in which case [[HomeObject]] will be the enclosing object literal. Of course, the [[Prototype]] of an object literal will always be Object.prototype so this isn’t terribly useful unless you manually reassign the prototype as is done below.

const obj = {

msg: 'Hello, ',

print() {

return this.msg + super.msg;

},

};

Object.setPrototypeOf(obj, {

msg: 'world!',

});

console.log(obj.print()); // Hello, world!

Emulating super properties

There is no way to manually set [[HomeObject]] on our methods, but we can emulate it by just saving the value and doing the resolution manually as shown below. It’s not as convenient as just writing super, but at least it works.

function Base() {}

Base.prototype.foo = function() {return 'foo in Base';};

function Child() {}

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child, Base);

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child.prototype, Base.prototype);

const homeObject = Child.prototype;

Child.prototype.foo = function() {return 'foo in Child';};

Child.prototype.bar = function() {

// super.foo();

return Object.getPrototypeOf(homeObject).foo.call(this);

};

const c = new Child;

console.log(c.foo()); // foo in Child

console.log(c.bar()); // foo in Base

Note that we need to use .call(this) to ensure that the super method gets called with the right this value. If the method has a property which shadows Function.prototype.call for some reason, we could instead use Function.prototype.call.call(foo, this) or Reflect.apply(foo, this), which are more reliable but verbose.

Super in static methods

You can also use super from static methods. Static methods are the same as regular methods, except that they are defined as properties on the constructor function instead of on the prototype object.

class Base {

foo() {return 'foo in Base';}

static bar() {return 'bar in Base';}

}

class Child extends Base {

foo() {return super.foo();}

static bar() {return super.bar();}

}

const obj = new Child;

console.log(obj.foo()); // foo in Base

console.log(Child.bar()); // bar in Base

super can be emulated within static methods in the same way as with normal methods. The only difference is that [[HomeObject]] is now the constructor function rather than the prototype object.

function Base() {}

Base.prototype.foo = function() {return 'foo in Base';};

Base.bar = function() {return 'bar in Base';};

function Child() {}

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child, Base);

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child.prototype, Base.prototype);

const homeCtor = Child;

const homeProto = Child.prototype;

Child.prototype.foo = function() {

// super.foo();

return Object.getPrototypeOf(homeProto).foo.call(this);

};

Child.bar = function() {

// super.bar();

return Object.getPrototypeOf(homeCtor).bar.call(this);

};

const obj = new Child;

console.log(obj.foo()); // foo in Base

console.log(Child.bar()); // bar in Base

Super constructors

When the [[Construct]] method of an ordinary constructor function is invoked, a new object is implicitly created and bound to the this value inside the function. However, subclass constructors follow different rules. There is no automatically created this value and attempting to access this results in an error. Instead, you must call the constructor of the superclass via super(args). The result of the superclass constructor is then bound to the local this value, after which you can access it in the subclass constructor as normal.

This of course presents problems if you want to create an old style class that can properly interoperate with new style classes. There is no problem when subclassing an old style class with a new style class, since the base class constructor is just an ordinary constructor function either way. However, subclassing a new style class with an old style class will not work properly, since old style constructors are always base constructors and don’t have the special subclass constructor behavior.

To make the challenge concrete, suppose we have a new style class Base whose definition is unknown and cannot be changed, and we wish to subclass it without using class syntax, while remaining compatible with whatever code in Base is expecting a true subclass.

First off, we will assume that Base is not using proxies, or nondeterministic computed properties, or anything else weird like that, since our solution will likely access the properties of Base a different number of times or in a different order than a real subclass would, and there’s nothing we can do about that.

After that, the question becomes how to set up the constructor call chain. As with regular super properties, we can easily get the superclass constructor using Object.getPrototypeOf(homeObject).constructor. But how to invoke it? Luckily, we can use Reflect.construct() to manually invoke the internal [[Construct]] method of any constructor function.

There’s no way to emulate the special behavior of the this binding, but we can just ignore this and use a local variable to store the “real” this value, named $this in the example below.

function Child(...args) {

const {constructor} = Object.getPrototypeOf(homeObject);

const $this = Reflect.construct(constructor, args);

// initialize subclass properties

$this.x = 43;

return $this;

}

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child, Base);

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child.prototype, Base.prototype);

const homeObject = Child.prototype;

const obj = new Child('some', 'args', 'for the superclass ctor');

console.log(obj.x); // 43

Note the return $this; line above. Recall that if a constructor function returns an object, that object will be used as the value of the new expression instead of the implicitly created this value.

So, mission accomplished? Not quite. The obj value in the above example is not actually an instance of Child, i.e. it does not have Child.prototype in its prototype chain. This is because Base‘s constructor didn’t know anything about Child and hence returned an object that was just a plain instance of Base (its [[Prototype]] is Base.prototype).

So how is this problem solved for real classes? [[Construct]], and by extension, Reflect.construct, actually take three parameters. The third parameter, newTarget, is a reference to the constructor that was originally invoked in the new expression, and hence the constructor of the bottom-most (most derived) class in the inheritance hierarchy. Once control flow reaches the constructor of the base class, the implicitly created this object will have newTarget as its [[Prototype]].

Therefore, we can make Base construct an instance of Child by invoking the constructor via Reflect.construct(constructor, args, Child). However, this still isn’t quite right, because it will break whenever someone else subclasses Child. Instead of hardcoding the child class, we need to pass through newTarget unchanged. Luckily, it can be accessed within constructors using the special new.target syntax. This leads to the final solution below:

function Child(...args) {

const {constructor} = Object.getPrototypeOf(homeObject);

const $this = Reflect.construct(constructor, args, new.target);

// initialize subclass properties

$this.x = 43;

return $this;

}

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child, Base);

Object.setPrototypeOf(Child.prototype, Base.prototype);

const homeObject = Child.prototype;

Final touches

This covers all the major functionality of classes, but there are a few other minor differences, mostly safety checks added to the new class syntax. For example, the prototype property automatically added to function definitions is writeable by default, but the prototype property of class constructors is not writeable. We can easily make ours non-writeable as well by calling Object.defineProperty() . Alternatively, you could just call Object.freeze() if you want the whole thing to be immutable.

Another new protection is that class constructors will throw a TypeError if you try to [[Call]] them instead of constructing them with new. Our constructor above happens to throw a TypeError as well, but only indirectly, because new.target is undefined when the function is [[Call]]ed and Reflect.construct() throws a TypeError if you explicitly pass undefined as the last argument. Since the TypeError is coincidental here, the resulting error message is rather confusing. It might be useful to add an explicit check for new.target that throws an error with a more helpful error message.

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed this post and learned as much as I did in the process of researching it. The above techniques are rarely useful in real world code, but it is still important to understand how things work under the hood in case you have an unusual use case which requires reaching for the black magic, or more likely, you’re stuck having to debug somebody else’s black magic.