When Type Annotations Are Code Too

Here’s a quick puzzle: What does the following Haskell code print?

main = putStrLn "Hello, World!"

This just prints Hello, World!, as you might expect.

$ ghc hello.hs && ./hello

[1 of 1] Compiling Main ( hello.hs, hello.o )

Linking hello ...

Hello, World!

Now let’s try something a bit trickier:

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import Foo(Foo)

todo = undefined

main = putStrLn $ show (if True then "Hello, World!" else todo)

Don’t worry about the irrelevant pragmas and imports and dead code. It turns out this one still prints "Hello, World!", just with quotes added due to use of show.

$ ghc hello.hs && ./hello

[1 of 2] Compiling Foo ( Foo.hs, Foo.o )

[2 of 2] Compiling Main ( hello.hs, hello.o )

Linking hello ...

"Hello, World!"

The above code doesn’t have any type annotations, but it’s considered good practice to add type annotations to top level items. So let’s add one to the todo variable, saying its type is Foo:

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

import Foo(Foo)

todo :: Foo

todo = undefined

main = putStrLn $ show (if True then "Hello, World!" else todo)

What does it print now? Oh, that’s easy. All we did is add a type annotation, and in fact, we added a type annotation to code that isn’t even reachable in the first place. Obviously, it’s still going to print "Hello, World!", right?

…right?!?

$ ghc hello.hs && ./hello

[2 of 2] Compiling Main ( hello.hs, hello.o )

Linking hello ...

これだからタイプクラスは!

What on earth is going on here?

Well, to start with, we can look at Foo.hs for some clues. It turns out that Foo is a custom type that prints “これだからタイプクラスは!” when showed:

module Foo where

import Data.String;

newtype Foo = Foo ()

instance IsString Foo where

fromString _ = Foo ()

instance Show Foo where

show _ = "これだからタイプクラスは!"

However, that still doesn’t explain why merely adding a type annotation to some unreachable code is enough to completely change the behavior of our program.

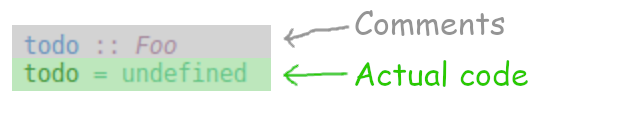

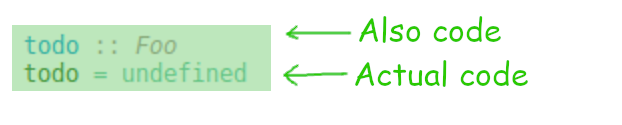

The fundamental problem is that programmers have a mental model of type annotations that looks like this:

However, the reality is more like this:

In dynamic-first languages like Typescript, or Python with Mypy, type annotations are descriptive. The code has independent meaning, and the type annotations merely describe what the code is already doing. However, most statically typed languages are not like that. In most statically typed languages, type annotations don’t describe the behavior, they determine the behavior.

For example, Haskell has a feature called typeclasses, which basically involves giving all your functions an implicit parameter that magically passes around a record of functions everywhere. Which of the invisible functions actually gets chosen is based on the static types, making type annotations an inextricable part of the program semantics. Even worse, type inference can propagate types backwards as in the example above, making type annotations a sort of super-code that can affect program behavior even if the annotated code is never actually executed.

Haskell provides a particularly extreme example, but every static-first language I am aware of has the same problem to some extent. If you’re forcing programmers to add type annotations anyway, the temptation of using those annotations to save programmers hassle by generating code for them seems to be too hard to resist.

Only the languages like Typescript where a static type system was bolted on to an existing dynamic language avoid this problem, and only because they had no choice in the matter. Unfortunately, this leads to a lot of problems, particularly once type inference comes into the picture.

Type inference vs Code inference

People often complain that type inference is complex and confusing and leads to bugs and so on. However, the problem isn’t with type inference, it is with code inference.

When types are merely describing the code, the details of the type inference algorithm are not too important. In the worst case, you can just ignore them, and the worst thing you have to worry about is being required to add extra annotations if the inference can’t figure out what you’re doing. There’s no such thing as a type inference algorithm that is too good - the more the compiler can deduce about your code, the better.

However, when static types define the code, type inference is suddenly fraught with problems, because it is actually code inference. Suddenly, every little detail of the type inference algorithm becomes part of the runtime semantics of your programs and every improvement to type inference makes the language more complex and harder to understand. Suddenly, too much type inference is a serious problem, because it leads to “inferring” code that was not intended, as in our demo at the start of the post.

The solution

Obviously, I think that programming languages need to make more of a distinction between code and facts about the code. Whether because it is easy or because designers couldn’t imagine things being any other way, this flaw is endemic in existing languages, but there is no reason why programming languages of the future have to be that way.

But wouldn’t that be too verbose?

One common objection is that this would make code too verbose. It’s true that if you take existing languages with code inference and remove it, programmers would have to write a lot more code in those languages. However, that’s just a consequence of the very design at issue!

One of the key issues in software engineering is choosing the appropriate level of redundancy. More redundancy protects against mistakes, but increases the amount of code and makes it harder to change. It’s important not to confuse the desired level of redundancy with the form that it takes. Make one thing less verbose, and people will compensate by increasing verbosity in other parts of the system and vice versa.

For example, in Rust, there are common polymorphic methods like .into() or .collect() which do different things depending on the desired (static) type. If you write them in isolation, you have to explicitly specify the types, but when the context already contains type annotations (such as returning a value from a function with an explicit return type annotation), you can leave them out.

Given the decision to always require return type annotations everywhere, it’s an easy decision to allow programmers to omit the types on into and collect calls, since requiring type annotations in both cases seems like an excessive level of redundancy. However, there’s no reason why things have to be this way. If you were designing a language from scratch, you could just as easily require programmers to specify which types they are collecting into, and not require return type annotations at all. It’s the same level of redundancy either way, but avoiding code inference like this gives your language much nicer properties.