My experience rewriting Enjarify in Rust

Last year I decided to rewrite Enjarify (a command line Python application) in Go and take notes in order to get data comparing the languages. Obviously, with a rewrite of an existing project, the resulting code won’t be as idiomatic as a project written from scratch, but I thought it was fair since Gophers are constantly trying to convert people away from Python for some reason, and doing a rewrite allows for a side by side comparison. Enjarify also has the advantage of end to end testing, making it easy to check that the implementations are in fact equivalent.

Anyway, the more I used Go, the more I hated it, and I ended up abandoning the project. Recently, I became interested in Rust, and decided to finish off the Go rewrite and rewrite Enjarify in Rust in order to get more experience with Rust and see if I would end up hating it like I did with Go. Below is my experience, as well as a comparison of the three versions.

All of the code discussed is available here.

Speed

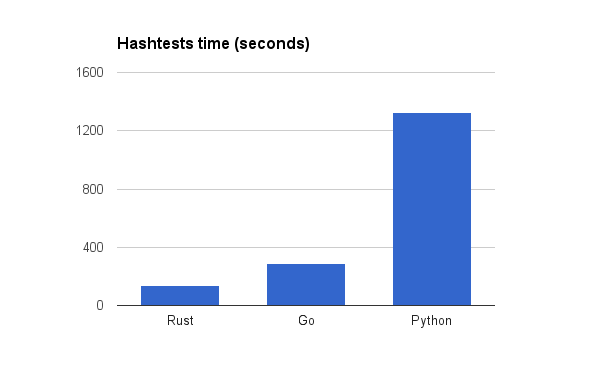

First off, a comparison of performance. For this, I ran Enjarify’s hashtests as a benchmark. This is a test that involves translating every test apk under every possible combination of options and hashing the results to detect regressions. I used CPython 3.4.3, Go 1.7, and Rust nightly (2016–09–02), all running on an i7–4790 with Linux.

Note that this test measured single threaded performance. I noticed that under default settings, the Go version was using 130–160% CPU, despite the code not having any goroutines. I think this is because the garbage collector runs in a seperate goroutine started by the runtime. At any rate, I did the tests with GOMAXPROCS=1, leading to a slowdown of ~8% over the multithreaded version.

Hashtests time: Rust 135 seconds, Go 290 seconds, Python 1328 seconds

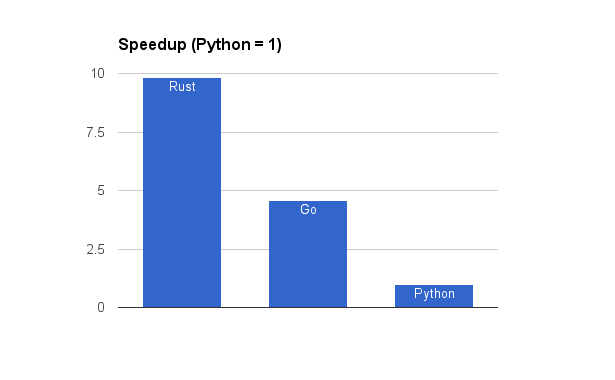

Here is a chart showing the speedup over Python (i.e. the reciprocal of the above).

Speedup: Rust: 9.8x, Go 4.6x, Python 1.0x

Unsurprisingly, Python is slower than Go and Go is slower than Rust. However, I was surprised by just how big the gaps were, especially between Go and Rust. I guess all those lifetime annotations and long compile times really pay off. I think this does emphasize how Go isn’t quite on the same level of “systems” language as C++ and Rust are.

Before all the Gophers come out of the woodwork to say stuff like “you can avoid the heap in Go if you really try”, the Rust version is implementing more or less the same code, so it shouldn’t matter either way. I didn’t deliberately make the Go version inefficient — I just tried to write something equivalent to the original Python in the simplest and most natural way that each language supports. I expect that most of the gain in Rust comes from optimizations that are impossible or infeasible in Go due to features like lifetimes, immutability and generics, or things that would unacceptably increase compilation time in Go (i.e. LLVM). Besides, there’s still lots of room for optimization in the Rust version too.

^ Update: I spent a while trying to optimize the Go and Rust code and wrote a follow up post with the results.

Note: I was hoping to include Pypy in this comparison, but unfortunately, it was much slower than even CPython. Pypy 3 used to be several times faster than CPython, but it appears that performance fell off a cliff some time last year and still hasn’t recovered. I guess I should stop recommending that people use Pypy with Enjarify.

Code Size

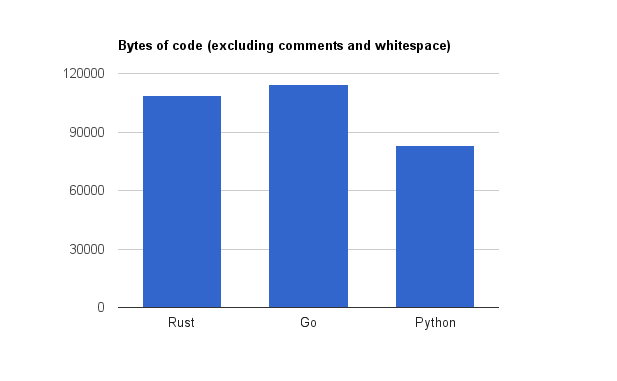

To measure code size, I stripped out comments and leading and trailing whitespace and added up the length of every nonempty line. I excluded generated code but included the code to generate that code. The script is here if you want to see the exact methodology.

Bytes of code: Rust 108847, Go 114180, Python 83013

Python, Rust, and Go had 2876, 3783, and 4971 lines of code respectively. The corresponding character counts are 83013, 108847, and 114180. I think the later is a better figure since it is less sensitive to brace style, but either way, the Rust code was larger than Python but smaller than Go.

Unsurprisingly, Go is the most verbose. What Rust loses with lifetime annotations and big generic type signatures, it gains from the emphasis on ergonomics, and from having actual abstractions, instead of requiring you to copy paste code all the time. On the other hand, Rust is nowhere near Python in conciseness, which makes sense, since Python is a dynamically typed scripting language.

Development Time

The Go rewrite took somewhere around 45 hours to complete. The Rust rewrite took 49 hours. Note that these numbers are biased towards Rust, because I had the advantage of being able to consult both the Python and Go code while writing the Rust version and the advantage of having already solved some of the problems involved during the Go rewrite.

I think a notable takeaway is that rewriting things takes longer than you expect, and that it takes a lot of time independent of the languages involved.

During the Rust rewrite, I spent a lot of time looking up the exact names and syntax of methods on Vec, Option, HashMap, etc. By contrast, with Go, there are no builtin methods at all. Some times I would do a web search to try to find the cleanest way to do something in Go, only to find out that there is no way and that you just have to brute force it with the limited tools available.

I also ran into several inscrutable lifetime/borrow errors, but that got easier as I went and accounted for only around two hours of wasted time total. I think the biggest time sink in Rust was a sort of death by a thousand cuts — all the time spent trying to get ampersands and refs in the right places, and other easily fixed, but extremely frequent, compiler errors.

However, this does show that Rust’s infamous learning curve isn’t that bad, especially compared to the much touted simplicity of Go. Furthermore, becoming familiar with a language is basically a one time cost. I wouldn’t be surprised to find that if this experiment were done by someone who is expert in Go and Rust instead of a beginner, the Rust version would be completed faster than the Go version.

Bugs

Since the original motivation for the rewrite was to compare Go and Python, I carefully kept track of the number of runtime bugs in the Go version to provide a bit of data for the perennial static vs dynamic typing debate, and figured I might as well do the same for Rust.

The Go version had 50 bugs that were caught during testing after passing the compiler. This includes both trivial bugs as well as several bugs that each took 30+ minutes to debug. For Rust, the corresponding number is 29. This does not include 3 intentional integer overflows where I forgot to use wrapping operations, since that wouldn’t affect correctness of the release build. Cases where overflow represented an real bug are included in the 29.

I hoped that Rust’s strong static typing would help reduce bugs, but sadly, it didn’t have much effect. A couple of the bugs I encountered in Go are completely impossible in Rust, but there were still a ton of bugs in the Rust version. Part of the problem is that bugs created while rewriting code are different from bugs that occur during normal coding. In this case, I was copying code that was already correct, so most of the bugs came from careless transcription mistakes which no type system could ever catch.

There is one other way language affects the number of bugs however — the mental burden incurred while translating the code. For example, consider the following lines of Python.

if isinstance(instr, ir.RegAccess) and not instr.store:

used.add(instr.key)

In Rust, this became

if let ir::RegAccess(ref data) = instr.sub {

if !data.store {

used.insert(data.key);

}

}

However, I originally forgot to include the !data.store check, leading to a bug. The problem is that in Rust, there is no way to perform the required “downcast” as part of a larger expression*. After writing the outer if let, I went off to shave a yak and completely forgot to type the second half of the if condition. If downcasting were a simple expression I could type without interruption, that almost certainly wouldn’t have happened.

^ I later learned about match guards, which could probably handle that, but I wasn’t aware of them at the time.

Implementation Issues

There are a number of features in Python that require more involved translation into Go or Rust. Here’s an overview of how I handled them.

Inheritance

Luckily, there are only two places in Enjarify that make nontrivial use of inheritance. The first, and easier case is ConstantPool.

There are two implementations of constant pools, SimpleConstantPool and SplitConstantPool. These are subclasses of an abstract base class, ConstantPool, which implements most of the functionality, while relying on a couple of abstract methods implemented by the subclasses.

In Go embedded structs cannot access the embedding struct so I had to create a struct for the base class, and an interface representing the methods implemented in the subclasses, then store that interface in the base struct. Then I created a struct for each of the subclasses embedding the base struct, and an interface representing the public interface of the whole thing. Plus all the wrapper methods required to implement the interfaces.

Luckily, in Rust, default methods in traits can call non default methods of the trait, making it possible to directly simulate an abstract base class. The Rust version has just one trait and two implementing structs, nearly identical to the original Python. There were only a few minor downsides — first, traits can’t have fields, so I had to use an accessor method instead. Second, trait objects can’t have generic methods, so I couldn’t use Into for overloading (more about this later).

The second, and much tougher case of inheritance is JvmInstruction. This has subclasses for various types of instruction (Label, RegAccess, PrimConstant, OtherConstant, Switch, and Other) as well as LazyJumpBase, which has two subclasses of its own (If and Goto). Additionally, the code makes heavy use of downcasting.

The Go version just replicated the Python inheritance hierarchy using interfaces and structs as before. However, this turned out to be a nightmare, and it’s not possible in Rust (without Any hacks) anyway. For the Rust version, I got rid of LazyJumpBase (duplicating the code it contained) and made JvmInstruction contain a giant enum.

There were a few annoyances to using an enum. The biggest problem is that it requires a lot of boilerplate and duplication. For example, here’s the enum definition that replaced (most of) JvmInstruction.

pub enum JvmInstructionSub {

Label(LabelId),

RegAccess(RAImpl),

PrimConstant(PCImpl),

OtherConstant,

Goto(GotoImpl),

If(IfImpl),

Switch(SwitchImpl),

Other,

}

If you want to be able to refer to the contents of the enum, have named fields*, or call methods, you need to create a separate struct definition. And that is in addition to the names of the enum constructors, leading to a ton of repetition.

^ Correction: enum variants can have named fields.

Apart from that, I needed to turn the methods that were defined in various subclasses into methods on JvmInstruction, with giant match statements over the contained enum. I also added helper methods like is_jump and is_constant since “isinstance” checks are a pain with the enum system.

Exceptions

Enjarify makes use of exceptions in two ways. The first is that if the generated bytecode is larger than the classfile limit, it throws an exception and retries translation with all the optimization options enabled. The second is that if any other exception is thrown while translating a class, it logs the error and continues with the next class, in order to handle invalid or malformed classes.

The good news is that Rust’s std::panic::catch_unwind/resume_unwind proved much easier to use than Go’s defer/recover. The bad news is that Rust prints out a stack trace when a panic first occurs rather than when a panic propagates to the top of the stack, so I had to set a custom panic hook to prevent that.

Shared Mutability

One thing I was surprised by was how borrowck-friendly Enjarify was already, given that it was written in Python, where aliasing and mutability are natural. Most of the code required only minor modification to borrow check, but there were a couple harder cases.

The first case was storing a (mutable) reference to the ConstantPool in IRWriter, which is kept alive until the entire class is done. The pool reference is only actually necessary while initially creating the IR, so I just split up and refactored the code, making it possible to borrow check. The result is cleaner, and it’s something I’d do to the Python version too if I had time, but it is notable that it required a big change to the code design.

The change of JvmInstruction from boxed to values and the removal of all uses of reference identity with it also removed another big source of aliasing.

Another issue I ran into was with a recurring pattern where I iterate over all the instructions and mutate each one while examining the previous instruction or two. This doesn’t actually violate the alias rules, but there’s no way for the compiler to know that. Instead, I came up with a workaround. I created a local variable outside the loop which stores a copy of the relevant data from the previous instruction, and updated it and the end of the loop body.

The last case is CopySetsMap. In this case, the shared mutability is necessary for the algorithm, so I just had to put everything in a Rc<RefCell> and endure the awful syntax resulting. At least it is only used in a very small part of the code. It’s a bit worrying though, since this is a very useful pattern, and I wish it was easier to do in Rust.

Reference Cycles

Once again, I was surprised by how little the code actually relied on reference cycles. I was prepared to have to poorly simulate garbage collection with TypedArenas, but as it turns out, there were already no nontrivial reference cycles in the design.

Pain Points in Rust

While I didn’t end up hating Rust, I did run into a lot of annoyances. Hopefully, most of these will be fixed in the future.

Reference Syntax is Confusing

It is almost impossible to guess where you need &s, refs, and so on, especially when dealing with iterator chaining and closures. If you can write code like this and have it compile on the first try, I will be very impressed.

let most_common: Vec<_> = {

let mut most_common: Vec<_> = narrow_pairs.iter().collect();

most_common.sort_by_key(|&(ref p, &count)| (-(count as i64), p.cmp_key()));

most_common.into_iter().take(pool.lowspace()).map(|(ref p, count)| (*p).clone()).collect()

};

for k in most_common.into_iter() {

narrow_pairs.remove(&k);

pool.insert_directly(k, true);

}

Why do the &s and *s and refs go where they do? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Part of the problem is that auto-deref means you can get by without the right derefs in some circumstances, but in others, doing the same thing fails for no apparent reason.

To make matters worse, there’s a huge inconsistency with some methods taking references and others taking values. This actually makes sense when you think about it. For example, map insert() and entry() take ownership of the key because they may need to insert it, while remove(), [], contains_key(), etc. don’t need ownership and hence take references for maximum flexibility. However, it’s still an additional burden to contend with when starting out, especially when you’re just dealing with simple Copy types and shouldn’t have to care.

The compiler pretty much tells you what you need to change, but I wish I didn’t have to go through the edit -> compile -> edit -> compile -> success cycle so much in the first place. This is the death by a thousand cuts I mentioned above.

Explicit Integer Casts

All those integer casts are annoying in Go, and they’re annoying in Rust too. One of the problems is that it forces you to constantly choose between using an integer type that represents the actual range of values stored and using the type that is most convenient syntactically (i.e just using usize everywhere). Part of that is that most of the values Enjarify deals with are specifically limited to 16 or 32 bits due to the Dalvik file format. I imagine that for applications which don’t do binary file parsing, it is a lot less common to have values bounded a priori.

I also wish that overflow semantics could be decoupled from storage size. Rust goes a long way towards this by requiring explicit wrapping operations when overflow is desired, but a full solution would probably require dependent types. Incidentally, I find it surprising that narrowing casts do not check for overflow. It seems like an oversight, though it might just be too hard to do in LLVM or something.

The worst part is that it seems to be ineffective at preventing bugs. There were several bugs in the Rust version related to integer casts. In one case, I called the wrong function, and it took a different width than the desired function. But it passed the compiler because I also forgot to cast the variables in question.

Besides, when nearly every call requires a cast, people will just automatically add them to shut the compiler up, defeating the purpose.

Lifetime Subtype Syntax is Not Discoverable

The combination of lifetime elision and automatic covariance deduction means that you rarely need more than one lifetime parameter. But in the case where you do, the syntax required is not discoverable.

For example, my IRBlock struct stores a mutable borrow of a ConstantPool object, but the references stored in the constant pool need to outlive the borrow, meaning that multiple lifetime parameters are required. Simply specifying multiple lifetime parameters isn’t hard. The part I found impossible was specifying that one of the lifetimes outlives another. It turns out that the syntax required is

struct IRBlock<'b, 'a: 'b> {

pool: &'b mut (ConstantPool<'a> + 'a),

// other fields omitted

}

The extra bound and parenthesis on the trait object was confusing enough, but the ‘a: ‘b thing wasn’t mentioned in any of the tutorials or guides I could find. In fact, the only reason I figured it out was due to stumbling across it in a Stack Overflow question about a tangentially related topic (whether structs can have where clauses).

Note that the usually helpful compiler is completely unhelpful here. It seems that the compiler suggestions are biased towards having as few lifetime parameters as possible, so if you mess up anything at all here, the resulting compiler error message will suggest removing the second lifetime parameter, which is obviously wrong in this case.

Lack of Overloading

In Rust, it is idiomatic to use generic Into parameters to overload methods, but unfortunately, I couldn’t do this in either of the cases where it was most useful.

ConstantPool works with Cow<bstr> internally because there are rare cases where I need to store an owned string. But almost all callers will be passing &bstr, so it would be nice to have methods accept that. Unfortunately, since ConstantPool is a trait object, generic methods can’t be used. I ended up prefixing the “internal” Cow methods with an underscore and creating “public” wrapper methods that take a &bstr. But this is an ugly hack that shouldn’t be necessary.

fn _class(&mut self, s: Cow<'a, bstr>) -> u16 {

let ind = self._utf8(s);

self.get(Class(ArgsInd(ind)))

}

fn class(&mut self, s: &'a bstr) -> u16 {self._class(s.into())}

Likewise, my TreePtr (a sparse persistent array implemented as a tree) uses usize for indexing internally, but the callers always use u16, so it would be nice to handle that. Unfortunately, usize inexplicably fails to implement From

I guess the idea behind usize not being From<u16> is that Rust might some day support an 8 bit platform, but that is still insane. It’s silly to cause so much pain to everybody today in the hopes of not breaking code in the event of a speculative future platform. The worst part is that most Rust code won’t work on an 8 bit platform anyway. In fact, even the standard library itself implicitly assumes that usize >= 32 bits, since Range<u32> implements ExactSizeIterator.

Poor Bytestring Support

Since most of the data Enjarify deals with is not utf8, I couldn’t use Rust’s native string types. Instead, I just defined type aliases for byte strings and used them everywhere.

pub type BString = Vec<u8>;

pub type bstr = [u8];

This works reasonably well, mainly because I don’t do much string manipulation beyond slicing and concatenation. But on the rare occasions where I do, I really missed the string convenience methods, which aren’t defined for Vec<u8> or &[u8]. Python by contrast, defines all the string methods for both unicode and byte strings. It also means that the default Debug implementation shows the values as a list of integers, rather than as strings.

On a side note, I never figured out how to make the compiler shut up about the naming of bstr, despite repeated searching. Nothing I try seems to work.

Update: The answer turns out to be #[allow(non_camel_case_types)]. I’m not sure how I missed that one. I did try several variations like #[allow(non_camel_case)], but I didn’t try putting _types at the end.

Reference Equality Is Verbose

In Rust, everything uses value equality, which is usually what you want. But in the cases where you do want reference equality, it is unnecessarily verbose. There is no equivalent of Python’s is operator.

That leads to code like

pub fn is(&self, rhs: &Self) -> bool {

match (self.0.as_ref(), rhs.0.as_ref()) {

(None, None) => true,

(Some(r1), Some(r2)) => r1 as *const _ == r2 as *const _,

_ => false

}

}

or even worse,

fn ptr(p: Option<&Rc<RefCell<CopySet>>>) -> *const CopySet {

match p {

Some(p) => p.deref().borrow().deref() as *const _,

None => null(),

}

}

// ...

let s_set = ptr(self.0.get(&src));

let d_set = ptr(self.0.get(&dest));

if !s_set.is_null() && s_set == d_set {

// src and dest are copies of same value, so we can remove

return false;

}

Note: After writing this, I realized it could be simplified by just taking a pointer to the outer RefCell, but it’s still gratuitously complicated either way.

No Enum Subset Types

When you have a value of enum type, it is treated as if it could be any variant of the enum, but often you statically know that it is a subset of the full enum. Usually this just causes a minor hassle with exhaustiveness checking, but it becomes a lot more annoying when the enum variants have different constraints.

For example with the constantpool::Entry enum, the Utf8 variant stores a Cow<’a, bstr>, but every other variant just stores a couple of integers. Nevertheless, the enum has a whole suddenly requires a lifetime parameter everywhere and can no longer be Copy, even when it is statically known to not be a Utf8. The lifetime parameter issue can be worked around to some extent by just using ‘static lifetime in these places, but there is no way to magically make it Copy.

Obviously, subset types would make the type system much more complicated, and I don’t even have any idea what kind of syntax you’d use to specify them. But it’s still a bit annoying.

Match Exhaustiveness Checking Doesn’t Handle Integers

For some reason, even if you match on a u8 and cover every case from 0 to 255, you still have to add a _ => unreachable!() at the end to satisfy the compiler. I’m not sure why it’s not handled, but it kind of defeats the purpose of exhaustiveness checking. With an unreachable default case, there’s no compile time protection in the event that you legitimately missed a case. Apparently, this is a known issue but can’t be fixed because of backwards compatibility.

Lexical Lifetimes

I know that Non Lexical Lifetimes are actively being worked on, but I figured I might as well highlight some cases where the limitations of the current borrow system caused awkward code.

let t = self.prims.get(src); self.prims.set(dest, t);

let t = self.arrs.get(src); self.arrs.set(dest, t);

let t = self.tainted.get(src); self.tainted.set(dest, t);

For example, here I had to split up the calls and assign it to a temporary variable. Lexical lifetimes prohibit the far more natural expression nesting, since the mutable borrow of the outer method call includes evaluation of the method arguments.

I’m not sure if this is related, but I also ran into a weird issue where Box::borrow_mut() doesn’t work but a manual reborrow does. This one actually stumped me so much that I had to resort to asking on Stack Overflow.

Clone Arrays are not Clone

For some reason, arrays of T: Clone are not cloneable. It’s ridiculous that I have to write code like this

fn clone<T: Clone>(src: &[T; 16]) -> [T; 16] {

[src[0].clone(), src[1].clone(), src[2].clone(), src[3].clone(), src[4].clone(), src[5].clone(), src[6].clone(), src[7].clone(), src[8].clone(), src[9].clone(), src[10].clone(), src[11].clone(), src[12].clone(), src[13].clone(), src[14].clone(), src[15].clone()]

}

A similar issue makes it impossible to initialize a large array, forcing me to use a Vec inside SplitConstantPool, even though the data has a known, fixed length.

Missing Features

I don’t know if I’m missing something*, but I couldn’t find any helper methods for copying or cloning elements in an Option or iterator chain. It can be solved with closures like .map(|x| x) (or its cousin .map(|ref x| x.clone())), but that just feels silly and unnecessary.

^ Update: I was missing something.

Likewise, it seems like Vec<Option<T>> -> Vec<T>, removing all the None elements, would be a common task, but as far as I can tell, it still requires a verbose iter/filter/map/collect chain.

^ Update: You can filter and map with a single call.

One other thing I missed is that there is no equivalent of Python’s int.bit_length(). Integers do have a leading_zeros() method, but without a way to get the corresponding width automatically, this is prone to mistakes. That is not an idle concern, because one of the 29 bugs I encountered was writing (64 - part63.leading_zeros()) for what turned out to be a 32 bit variable, rather than 64 bit like I thought.

Third Party Dependencies

The Python and Go versions used only the standard library, but for the Rust version, I had to use a bunch of third party crates. Specifically, byteorder, getopts, lazy_static, rust-crypto, and zip. Cargo makes this very easy to do, but you still have to take the extra time to decide on a crate and read the documentation, and third party dependencies make me slightly nervous (cf. the left-pad fiasco).

Additionally, the zip crate only has basic functionality. For example, it might be useful to use a fixed timestamp for output jars to make the output deterministic. Python and Go support this, but the zip crate doesn’t appear to.

Whenever people said Go is batteries included or has a comprehensive standard library before, I’d always scoffed, since it is hard to take a standard library seriously when it doesn’t even have any collections, but now I can see what they mean. Rust has tons of useful collections and algorithms standard, but pretty much nothing else, while Go is the opposite. Python of course has both.

No try! for Option

For the Rust version of the mutf8 decoder, I used custom iterator adapters. Iterators return Options, not Results, but unfortunately, there is no equivalent of the try! macro for Option. That meant that I had to copy paste the same four lines of code over and over, as you can see below.

impl<'a> Iterator for FixPairsIter<'a> {

type Item = char;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<char> {

let x = match self.0.next() {

None => { return None; }

Some(v) => v

};

if 0xD800 <= x && x < 0xDC00 {

let high = x - 0xD800;

let low = match self.0.next() {

None => { return None; }

Some(v) => v

} - 0xDC00;

char::from_u32(0x10000 + (high << 10) + (low & 1023))

} else {

char::from_u32(x)

}

}

}

Debugging

The default stack traces printed on panic are way too noisy. There’s typically a dozen stack frames in the guts of Rust at the top before it gets to the important part, the user code that triggered the panic. Also, there’s a lot of visual noise. It’s hard to find the important part, the file and line number, amidst all the random hex addresses. I wish Rust did what Python does and print out the relevant snippets of source code in the stack trace.

Another annoyance is that even for debug modes, compilation takes a while (around 8 seconds for Enjarify) which is a big roadblock when you’re debugging in an edit->compile->run cycle. My ideal scenario would be a Python-like interpreter for debugging Rust, with no compilation required, and a nice REPL and pdb style debugger built in. (I guess I’m biased since I use Python so much).

Index is Broken

The Index trait is broken, because it requires returning a reference to the result, limiting it to collections that actually store a corresponding element. You can’t create and return values on the fly. This means that I couldn’t overload [] for Enjarify’s custom sparse array type and had to make do with get() and set() instead. This is a known issue, and I had already read about it before starting the rewrite, so I didn’t waste time attempting to implement Index, but it is still an annoyance.

Conclusion

If you have a Python application and are considering rewriting it due to the siren song of static typing, you should seriously reconsider, at least if you have more tests than developers. Rewriting anything takes a lot of time and causes lots of bugs, going from Python to less expressive language means an increased maintenance burden. But if for some reason, you still want to rewrite it, please don’t pick Go. Rust is better in pretty much every way.

Apart from that, I hope that my experience shows the gaps that Rust still needs to fix.

The opinions expressed here are solely my own and do not represent my employer or any other organization.