Parallelizing Enjarify in Go and Rust

Last year, I rewrote Enjarify in Go and Rust in order to learn more about the languages and compare the difficulty, verbosity, performance, and error-proneness of the languages, and I wrote a post detailing my findings. For simplicity, I only measured single-threaded performance, but a number of commenters felt that this was unfair to Go because easy concurrency is one of the core selling points of the language, by which they presumably meant parallelism, Rob Pike not withstanding. Therefore, I decided to parallelize the code and write a new post detailing the results.

Optimization

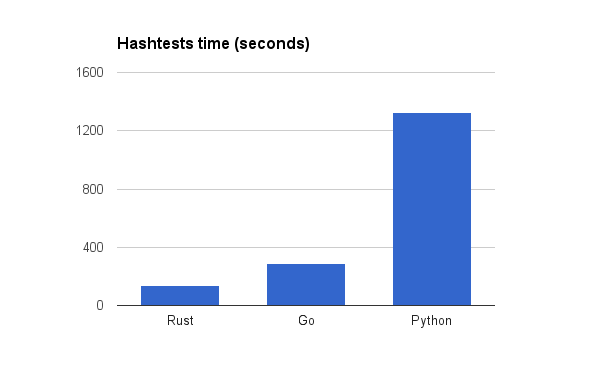

First off, here are the performance figures from the original post.

Hashtests time: Rust 135 seconds, Go 290 seconds, Python 1328 seconds

The original post just benchmarked my code as is. However, there were several ideas for optimizations I had while writing the Rust version that I wanted to try backporting to the Go version, and the Go version also had a bunch of code which was written to be simple rather than fast. I decided to spend a while trying to optimize the (single threaded) Go and Rust code to see how much of the performance difference was inherent rather than due to suboptimal implementation choices.

As it turned out, I was able to make the Go version much faster, although not for the reasons I expected. For example, hand monomorphizing TreeList led to only a small speedup and many microptimizations had no measurable impact or made things worse. Meanwhile, the single biggest improvement came from a change that I initially expected to slow things down. Even with a profiler, it’s hard to guess how code can be sped up, though I imagine it gets easier with experience. Meanwhile, the Rust version was already a lot faster, but I was still able to find two improvements.

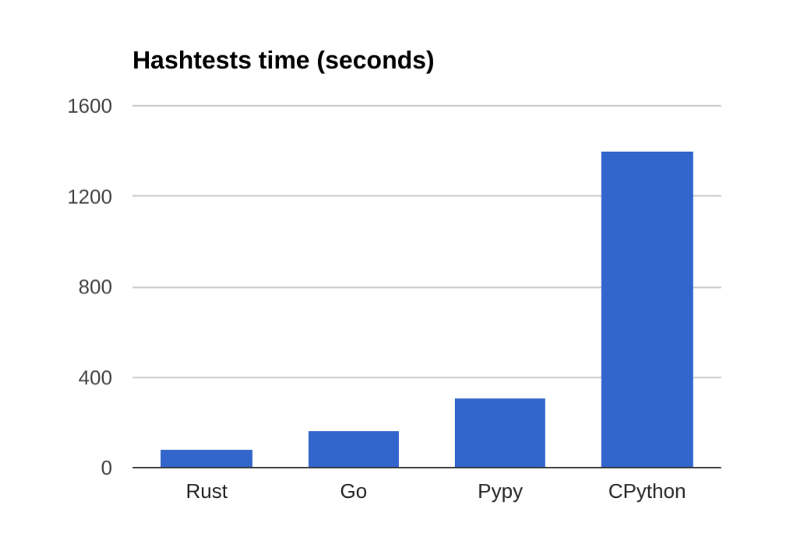

Apart from that, I also upgraded language versions, but this had mostly negative effects. CPython got bumped up to 3.5.2, which actually made it about 5% slower. Upgrading to latest Rust had no measurable effect. Go 1.8rc1 was about 10% slower, so I stuck with 1.7. Note that that is only for the original single threaded benchmark- on the later parallel version, there was no measurable difference between 1.7 and 1.8, but I used 1.7 numbers for consistency. The big winner was Pypy. In my previous post, Pypy was omitted due to being slower than CPython, but whatever bug that was got fixed in the interim, so Pypy is now included.

Rust: 82.5 seconds, Go 165 seconds, Pypy 310 seconds, CPython 1402 seconds.

Rust got 64% faster while Go got 76% faster, decreasing the Go/Rust ratio from 2.15 to 2.0. It is also interesting that Pypy was nearly as fast as the unoptimized Go version from the original post. This indicates that if Pypy is available and you don’t know much about optimizing Go and only single threaded performance matters, you may not actually see speed benefits from rewriting Python code in Go, though the Go version would still be faster for short running tasks due to the lack of a JIT warmup.

Anyway, with that as a baseline, it was time to parallelize the Go and Rust code. I didn’t bother with the Python version for obvious reasons.

Design

The first question when parallelizing is what and where to parallelize. Luckily, the hashtests benchmark I’ve been using is already embarrassingly parallel. It consists of running Enjarify on each of 7 test files with all 256 possible combinations of passes enabled, and printing out a hash of the output. I originally created it to detect unintentional changes in behavior while working on Enjarify, but it also serves as a convenient self contained benchmark.

The obvious approach would be to parallelize the hashtests loop and run the 1792 tests in parallel. However, this seemed a bit artificial since it wouldn’t lead to any improvements for normal usage of Enjarify. The other obvious place to parallelize is the main translation loop, which translates each class in the provided dex file(s) into a Java classfile, a process which is completely independent of the other classes. There is no point in trying to parallelize at a finer granularity because the translation of each individual class is inherently sequential due to all the methods and fields in the class sharing a single constant pool.

Parallelizing the translation loop would work well for normal usage of Enjarify, where you typically translate a single apk file with thousands of classes, but wouldn’t help much on hashtests, where a single file with 1–6 classes is translated hundreds of times. Therefore, in my experiments, I decided to require both the hashtests loop and the translation loop to be parallel.

Go

Go’s core concurrency primitive is channels. In fact, it is so important that it is one of only three generic types in the language and has its own dedicated syntax. The standard library also provides the usual mutexes, atomics, etc. but my aim was for the simplest and most idiomatic approach possible, and that meant sticking to channels.

The obvious approach is to spawn a goroutine per task and have them all write the result to a single channel when done. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work because the results will arrive out of order. After doing some research on which patterns are considered idiomatic, I decided to go with the semaphore channel pattern.

This involves allocating a slice to hold all of the results in advance, and having each goroutine write the output at a predetermined location in that slice. They then send a zero sized type on the channel to indicate completion. The parent thread receives on the channel once per goroutine and then reads the slice that now holds all the output.

And of course, I did the same thing with the hashtests loop. This is slightly more complicated because printing out the hashes and computing the final hash must be done in order. Therefore, I split the loop into two parts — one which does all the actual computation, and then a second loop which waits until that is done and prints out the results in order.

Rust

Unlike Go, Rust leaves concurrency up to libraries. In this case, I decided to use Rayon. Before any gophers complain that that is unfair, I did spend a while looking for equivalent Go libraries but couldn’t find any.

Rayon handles all of the buffering and ordering of results for you, so it is a lot nicer to use than the Go version. In this case, most of the work came from rewriting my loops in iter/map/collect style. Once that was done, the actual parallelization was simply a matter of importing Rayon and changing iter to par_iter.

Note: The Go code also has equivalent panic handling boilerplate, but it is elsewhere in the code and hence not shown above. In general, I tried to keep the high level design as similar as possible between the three versions.

As before, I had to split up the loop in hashtests and put the print statements after all the results had been calculated. However, the Rust version required larger changes in order to get rid of the nested loop. There’s probably a way to make a nested loop into a Rayon compatible iterator, but I didn’t feel like trying to figure it out, so I rewrote the code with a single 7*256 iteration loop using modulus to get the original indices. Apart from that, I moved the loading of the test files out of the loop to make the lifetimes easier.

Results

On my 8 core machine (4 physical cores), the resulting Go code went down to a median of 48.0 seconds, while the Rust code went down to 23.7 seconds. This means both had a speedup of around 3.4x. There are several possible explanations for the lack of full scaling — Amdahl’s Law, synchronization costs, cache contention between the cores, etc, but I didn’t try to investigate that in depth. It is surprising that the speedup factor is roughly the same between the two languages though, since there is no a priori reason why any of those factors would be the same in both cases. At any rate, this means the Rust code was roughly twice as fast as the Go code in every benchmark — unoptimized, optimized, and parallel.

Bonus Round — Streaming Results

The parallel code above resulted in a nice speedup, but it has the disadvantage that the command line output isn’t interesting to look at. The sequential version printed out every line as soon as it could, leading to a continual stream of results, but the parallel version doesn’t print anything out at all until everything is done.

Therefore, I decided to see if I could fix that while still keeping the computations parallel. Obviously, there still has to be some buffering, but it should be possible to print out say, the first line as soon as the first result is ready, then wait for the second result if it isn’t done yet, and so on.

Go

Streaming was easy to implement in the Go version, although it required a separate channel per goroutine, which felt kind of dirty. In keeping with Go’s mantra of “share memory by communicating”, I decided to have a single channel for output, with ordering ensured by passing that channel between goroutines, via a seperate set of channels. Each goroutine gets passed two channels, with the output end of one channel hooked to the input end of the channel passed to the next goroutine.

The translation loop in main.go was left untouched.

Rust

Streaming proved much harder to implement in the Rust version. First off, Rayon currently has no support for this, so I decided to rip out Rayon and try Futures instead. I could have left Rayon in for the translation loop and only used futures for the hashtests loop, but I worried that having multiple libraries around with independent threadpools might cause problems. (Ironically, the opposite turned out to be the case).

The obvious way to implement streaming with futures is to build up a list of futures, each representing one iteration of the loop. Then you just wait on the first one, then the second one, etc. This was actually easier than I expected (no boxing required).

Unlike Rayon, Futures requires you to explicitly create a threadpool, rather than implicitly creating a global threadpool, but that wasn’t a big deal. The real problem was the lack of scoped threads.

Like most Rust libraries, Rayon and Futures::CpuPool take closures that represent the work to be done. In Rayon, these are scoped — the work is guaranteed to complete before you return, and hence the closures can safely hold stack references. In fact, they can basically do anything that non-closure code in the same place can do, and Rust’s closure type inference means that it just works.

Unfortunately, Futures does not support this. CpuPool::spawn_fn() has a 'static bound, meaning that the closures passed in can’t reference any stack data, since it thinks they might outlive the spawning thread.

For the outer hashtests loop, this wasn’t too hard to work around. I just shoved the pool and the testfiles inside of Arcs. It did take me a while to figure out the appropriate way to clone and move these into the closure though, since rustc’s error message in this case is completely unhelpful.

The translation loop on the other hand closes over a DexClass<'a>, which isn’t so easy to fix. DexClass is parsed from the input dex file, and it has borrowed references into said file. Unfortunately, all of the dex parsing code and all of the code that uses the parsed data assumes it is working with borrowed references. There’s no safe way to make it static without making major code changes, which I wasn’t willing to do, especially since it’s an unnecessary pessimization in the first place.

With a heavy heart, I turned to the unsafest of the unsafe, mem::transmute to transmute away the lifetime. In this case, it should be safe, because all the futures are waited on while the borrowed data is still alive, but it is very easy to mess up and there’s no way to know.

With all that out of the way, the code finally compiled… and ran… and didn’t produce any output.

I’m still not sure what exactly the problem was, but after some debugging, I eventually guessed that using the same thread pool for both loops was somehow causing a deadlock. I changed it to run each translation in a separate threadpool, and it finally worked.

Final results

Both versions stream results to the console with no decrease in performance. The Go version is a bit “jerky” — it will pause for a while, then print out a bunch of results at once, and then pause again. This isn’t surprising as the results are being executed in parallel and buffered under the hood, but it is slightly disappointing. Using an unbuffered output channel reduced the jerkiness but didn’t eliminate it.

The Rust version is only slightly jerky. You would have to watch very closely to tell it apart from the original sequential version, apart from the fact that it now runs 3.5x faster.

I don’t think the jerkiness proves Rust is superior — it’s probably just chance which scheduling algorithm happens to be better here, but it was an interesting difference.

The Rust version also went from 23.7 seconds to 23.1 seconds. I’m not sure whether this is a Rayon vs CpuPool thing or whether it is due to printing out the results in parallel with the computations.

Conclusion

Parallelization isn’t too bad in either language. Each has its own annoyances. In Go’s case, this is due to not having a real type system. In Rust’s case, it’s due to the libraries being immature and not doing everything you might want.

Similar to before, my experience with Go is that you always know what your toolbox is, but that toolbox isn’t very big and you have to spend time thinking about what the least ugly way to build what you want is. With Rust, you spend your time researching libraries and apis, but the resulting code is nicer than the Go equivalent.

Apart from that, a lot of the repetitive work in Go is spent reinventing the wheel, which is easy, but unnecessary. Rust solves this through type inference, generics, ergonomic builtins, etc. Rust also requires a bunch of repetitive work, but it is at least done in the service of interesting problems — proving safety, eliminating allocations, etc. Go solves this by not even trying.