How I came second out of 999 in the Salem Center prediction market tournament without knowing anything about prediction markets, and what I learned along the way - Part 1

Last August, the Salem Center at the University of Texas announced a year-long prediction market tournament in partnership with the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology in an attempt to find people who are good at predicting the future. Despite having absolutely no experience with prediction markets, I decided to give it a try and amazingly managed to place second out of nearly a thousand participants.

This post is divided into two parts. The first part (what you’re reading) begins with a brief description of how the tournament worked, then the overall lessons I learned while participating in the contest. The second part will be a detailed chronological account of the contest from my perspective, explaining how my strategy changed over time.

How does a prediction market tournament work?

Every player starts with $1000 in imaginary money and can bet on various questions like “Will Republicans win the House of Representatives?” or “China Reaches 100,000 Covid Cases by Winter?” to increase their imaginary money, with the player who has the most money at the end of the year being the winner.

However, the odds of the bets are not fixed. Instead, they take the form of a prediction market. In a prediction market, there is a “market price” which goes up and down depending on how people bet.

To place a bet, you buy “shares” in the market, with the number of shares depending on the current market price. For example, suppose that the current market price for “Will Republicans win the House of Representatives?” is 0.80 (i.e. 80%), and you think that it will happen. In this case, you can bet $1000 on YES and receive 1000/0.80 = 1250 YES shares, which will each pay out $1 if the Republicans win the House, and thus, you will end up with $1250 if you were right and $0 if you were wrong. Alternatively, if you think that it won’t happen, you can bet on NO instead. In this case, you would receive 1000/(1-0.80) = 5000 NO shares, so you will end up with $5000 if Republicans don’t take the House and $0 if they do.

Note: In reality, the number of shares you would receive is much lower than this due to transaction fees and slippage, but I’m ignoring that for the sake of simplicity in this example.

Additionally, the market price changes over time. Every time someone bets on YES, the price goes up, and every time someone bets on NO, the price goes down. Therefore, you get better odds if you bet the opposite of the way most other people have bet.

Lastly, you can also sell your shares early, instead of waiting for the market to resolve and pay out to the winners. For example, suppose you bought 1250 YES shares for Republicans to take the House, and then a bunch of polls come out that favor Republicans and everyone thinks they are more likely to win, so they bet YES as well and increase the market price from 0.80 to 0.90. Then you could sell your shares early for 1250 * 0.90 = 1125 (again, ignoring transaction fees and slippage), and thus make a $125 profit off of your original $1000 bet.

If it all came down to just one bet like this, the contest wouldn’t be very interesting. Fortunately, the real contest took place over the course of a year with 91 markets in total to bet on, and people could reinvest the winnings from early markets in later markets to further increase their money (assuming they managed to consistently predict the outcomes correctly.)

Over the course of the year, I learned a number of lessons while participating in the contest. Here are my top 15 takeaways.

1. It’s not just about predicting the outcomes

You might think that a prediction market contest is all about who can most accurately predict the outcomes of the markets.

In reality, Salem is a game where the objective is to maximize your score (or rather the ordinal rank of your score), and predicting the outcomes of the questions is one skill that is important for doing this, but it is not the only one. Among other things, you need to be quick to find relevant news, you need to be able to predict when the markets resolve, you need to correctly allocate your bets taking into account transaction fees and opportunity costs, and you need to predict what other players will do.

2. Breaking news is easier than predicting it

The fastest way to make a profit is to find important relevant news which will determine resolution or massively swing the market price and be the first to (correctly) trade on it.

Of course, this is easier said than done. The markets I did best in involved following election results (for the Wisconsin Supreme Court in April and the two Turkish elections) and the Supreme Court decisions, both cases where the information would come out at a relatively predictable time, though that of course means that everyone else is also watching and racing you, trying to do the same thing.

In other markets, such as “Will PredictIt Survive?” or “Elon Appoints New Twitter CEO?”, information would come out of nowhere with no warning, and I never had any luck with those. I’m not sure how other people did it, but it presumably involved following the right accounts on Twitter all day. But it doesn’t seem remotely feasible to do that for months on end across many different markets, so it was probably largely a matter of luck.

The easiest way to make a profit is to wait for someone else to find news and spike the market, and then buy into that market as well before it resolves. However, the returns from doing so are relatively small.

3. Betting is often terrifying

Following the news and being the first to bet on it sounds like easy money after the fact, but in the moment, it is terrifying. Sure it might look like the election is effectively over and there’s no way Vallas can win, but you don’t actually know that for sure. Sure it might look like the Supreme Court just banned race in college admissions, but a lot of people disagree and are betting against you, and maybe the Salem Center will agree with their interpretation and resolve against you. Are you really going to lose everything after a year of hard work, just like that?

It doesn’t help that you know that other players are likely watching the news too and trying to race you, so there’s a strong incentive to be bold and act more confident than you actually are. And even when things seem really safe, you can never be completely sure until the market resolves.

Once it resolves of course, you’ll immediately start beating yourself up with the benefit of hindsight, cursing your past self for not buying more/less of that obviously good/bad trade.

4. Predicting when a market will resolve is important too

This was one of my first major lessons, and one I learned the hard way. On November 16th, I noticed that the “Gay Marriage Bill in 2022?” market had spiked, and assuming that it was about to resolve and I could make a quick buck, I FOMO’d in with my entire balance ($3166) at a market price of 99.0%. As it turns out, the market did resolve YES in the end, and I made a profit of $32. So that was a smart bet, right?

Far from it, in fact. One issue is that the market price dropped into the 90s immediately afterward, and reached as low as 82.4%, so I could have made massively more profit if I’d just waited a bit to invest. But the other issue is the opportunity cost of having your money locked up for long periods of time.

As it turned out, the market didn’t resolve until December 13th, nearly a month later. For a month, I was completely locked out of doing anything on Salem, and just had to watch helplessly and pray that the market would resolve soon. In particular, this meant that I was unable to participate in the Georgia senate runoffs market at all, and thus missed out on the potential profit there.

And yes, before someone complains, it was technically possible to sell my shares early instead of waiting for resolution. However, doing so would have incurred massive losses, so it wasn’t a real possibility. (Another player, Josiah Neeley, did sell out early at a huge loss, presumably due to not understanding this.)

I actually did already understand the importance of resolution timing, and before investing, I quickly checked Google and saw a news article that the gay marriage bill had passed a critical hurdle in the Senate. I thought it was odd, since that meant there were several more steps before it actually became law, so it seemed like the market might take a while to resolve, but I assumed that everyone else knew what they were doing and suppressed that little voice and FOMO’ed in. Big mistake.

Other examples

Gay Marriage was the most dramatic example, but there were several other cases where I lost out due to failing to predict market resolution time.

On the afternoon of March 30th, the “Will Donald Trump Be Indicted for a Crime by July 2023?” market spiked due to news of the Bragg indictment. I actually happened to check Salem relatively early into the spike and considered buying in myself. However, I worried that the market might not resolve until the indictment was officially announced or something, and that that might take several days to happen.

Ordinarily, several days wouldn’t matter much, but this was on March 30th, and there were three other markets set to resolve on March 31st. If the indictment market resolved immediately, the correct move would be to buy in, but if it took several days to resolve, then that would be a bad idea because it would mean missing out on the profit from the March 31st markets. Therefore, I stayed out, and thus missed a bunch of potential profit when the indictment market did in fact resolve soon afterwards.

The next day, I was caught out again by the “Donald Trump Back on Twitter?” market, which said “This market will settle as YES if an account belonging to former president Donald Trump tweets at least one time between the opening of the market and March 31, 2023.” The market was originally set to close at midnight on March 31st, implying that March 31st was included in the time period of the bet. However, they randomly resolved it at 11:01am on March 31st instead, presumably interpreting the description as requiring Trump to tweet before March 31st. Since I thought that it wouldn’t resolve until later that night, I waited to put my money in until the evening and thus lost out on the potential profit when it unexpectedly resolved early.

Lastly, I also failed to guess when the “Elon Appoints New Twitter CEO?” market would resolve. The market spiked on the afternoon of May 11th, with the news that Elon was appointing a new CEO for Twitter, and I bought into that spike. However, it wasn’t clear to me whether the market would resolve immediately based on the announcement or would only resolve when the new CEO took office which wouldn’t be for another six weeks.

In the latter case, shares in the CEO market weren’t worth 100% because there would be a lot of other markets in the next six weeks that you’d miss out on. Presumably, everyone else took this risk seriously as well, because the market closed at only 92% when it resolved the next morning, rather than jumping up to 97-99% before resolution as would happen when everyone believed it would be resolving imminently. In fact, my final transaction before resolution was actually a small sale at 92%, to try to free up money in case it did get locked up for six weeks. If I’d known that it would be resolving the next morning, I’d have instead gone all in and made more profit.

5. There’s a risk that markets won’t resolve when they’re supposed to

There were a bunch of markets that were set to end on February 28th, as well as one market set to end on March 1st. Most of the time, Salem resolved markets relatively quickly, but for unclear reasons, they failed to resolve the end-of-February markets in a timely manner.

Instead, these markets were just stuck in limbo for several days before people finally got their money. This one didn’t really affect me, since I was not actively playing at the time anyway, but I’m sure it annoyed the people who were. It also means that anyone who was planning to reinvest the profits from the Feb 28th markets into the March 1st market before it closed were unable to do so.

6. Transaction fees are significant

When I first joined, I had no idea about the inner mechanics of the markets and only knew “bet on things you think will happen and against things you think won’t happen”. Following the November midterm elections, I was catapulted onto the leaderboard and realized that I now had a real chance of winning and needed to take things more seriously, so I immediately set about researching how the markets actually worked.

The Salem contest was run on a platform called Manifold Markets, and Manifold is open source, so I was able to find the source code that determined how market prices changed in response to bets, and how transaction fees were calculated.

Transaction fees are determined by the following formula:

fee = rate * bet * (1 - final market price)

Where rate is a site-specific setting (which I finally got around to reverse-engineering in early January and found to be 0.1), bet is the amount you’re betting, and final market price is what the market price would be after your bet if there were no transaction fees.

For example, suppose the current market price is 0.5 (50%) and you are betting an infinitesimally small amount so that the market price won’t change at all. In this case, the final market price is still 0.5, so the fee is just 10% * (1 - 0.5), or 5% of your bet.

Therefore, you only get 95% of the amount of shares you should have, which means that if you bet YES, you’re effectively paying a price of 1/.95 * 50% = 52.63%. In other words, the amount of YES shares you get at a market price of 50% is the same as the number of shares you would get if the market price were 52.63% and there were no transaction fees. Likewise, if you buy NO, the effective market price is 47.37%. Therefore, at a market price of 50%, there’s an effective bid-ask spread of 5.26%, just from the transaction fees alone.

Note: This is only from transaction fees. For any real transaction, your bet would also move the market price, further decreasing the amount of shares you get, which is called slippage.

As an example of how punishing transaction fees can be, there was one time when I accidentally bet $50 that I didn’t intend to and immediately sold the shares back. Despite immediately selling back my bet with no intervening market movements, I only got back $43.75. The transaction fees had just cost me 12.5% of my original bet, just from buying and selling it back.

Limit Orders

The above all applies to normal market orders. You can also place limit orders, where you specify a fixed price (sadly only whole percent numbers were allowed) and then if the market price reaches your limit, trades will automatically trade against your limit order at the specified price. The nice thing about limit orders is that there are no transaction fees for the buyer or seller.

One consequence of this is that when the market is at a limit order, trading against it offers a much better deal than the market price would indicate. For example, if you want to buy YES and the current market price is 52.0% with a NO limit at 52%, this is actually a better deal for you then if the current market price were only 50.0% but there were no limit order (which would result in an effective price of at least 52.6%).

This also means that occasionally, the market price getting worse will improve the deal. If the current market price is 51.9% and there is a NO limit order at 52% and you want to buy YES, the effective price you’ll get is whatever the transaction fees are on top of 51.9%, probably around 54%. But once you buy a tiny amount of YES, the market price will hit 52% and trigger the limit order, at which point the marginal price is exactly 52% with no transaction fees.

Split bets

Another little-appreciated consequence of the transaction fee formula is that making a single bet will have very slightly lower transaction fees than splitting the same amount of money into multiple consecutive bets, assuming all else is equal. This is because the transaction fees are calculated based on the final market price (or rather what the final market price would be if there were no transaction fees). Making your bet in one big transaction moves the market more and thus has lower transaction fees for the entire bet.

Overall, I doubt this factor made a big difference, but it encouraged me to try to be bold and make fewer, larger bets. Some players, on the other hand, did the exact opposite. The player 50P in particular would always make their bets in the form of a long string of really tiny consecutive bets.

I didn’t care much if other players inflicted unnecessary transaction fees on themselves, but it was really annoying just due to clogging up the bet history with massive amounts of spam, making it hard to see what was actually going on in a market. Eventually, I got annoyed enough at 50P’s antics that I left a comment explaining how splitting up bets increases transaction fees. They explained that in addition to the normal UI for making bets, where you type in the amount you want to bet, there is apparently also a button in the UI you can click to make a $10 bet, and they were spamming that button instead of using the normal UI. Sadly, the information about transaction fees failed to change their behavior for long.

50P wasn’t the only person to spam the $10 bet button. The most extreme case was Greg Simitian, a new player who joined right before the end of the contest and put their entire starting $1000 on YES on Debt Ceiling (spiking the market price from 7.0->28.4%) in 100 individual bets of $10 each. Just clicking that button 100 times must have been really annoying for them, as well as everyone else. It’s a shame Salem didn’t just disable that button.

Unfortunately, the numbers here are hard to calculate because Malte Schrödl (5th place finisher) had placed several NO limit orders at 13%, 15%, and 20% in case of precisely such an eventuality, and thus some of Greg’s bets were against a limit order and the normal rules don’t apply. However, if we take only Greg’s first 23 bets, before he hit the first limit order, Greg got a total of 2221.97006487 YES shares from his first $230. If he had instead bet $230 in a single bet, he would have gotten 2228.07008541 YES shares, a 0.27% improvement thanks to the lower transaction fees. So it’s not a terribly significant factor, but it is there.

As another example, the night before the Q2 GDP market resolved, I bet $500 on YES and then three hours later (with no intervening market movements), another $500. I got a total of 1127.69167347 shares, but if I had made a single $1000 bet, I would have gotten 1128.70022288 instead. Of course the whole reason I made split bets was because I was originally only willing to bet 500 and only changed my mind hours later. And the advantages to single bets are extremely tiny and swamped by intangible factors such as the chance that someone else will bet on the market in the meantime and move it in your favor or against you. Overall, I think I erred by worrying too much about transaction fees on split bets.

Transaction fee strategy

For better or worse, I tried hard to avoid transaction fees. This mostly meant avoiding trading as much as possible and making decisive large trades when I did bet.

I also used limit orders to sell my bets wherever possible, though this does have downsides. First, you only come out ahead on transaction fees if your limit price is within ~3% of what the market price would have been anyway. But more importantly, you’re completely at the mercy of waiting for other people to trade against your limit order, which may not happen when you want it to. Lastly, there’s the danger that you’ll forget to cancel old, obsolete limit orders. There was one time when I forgot to cancel an old limit order and ended up trading against my own limit order, which was pretty embarrassing.

Relying on limit orders to sell my shares was a double-edged sword. Sometimes noone would cash me out when I really needed the money. And sometimes that was even a good thing. In the week before the Supreme Court decisions, I put limit orders at the market price on all my holdings in an attempt to sell them and free up money to bet on the Supreme Court. I sold some of my shares that way, but not all of them, which turned out to be fortunate, because in retrospect, it was a terrible deal, and the shares I sold would have made way more money if I kept them than I could have made betting on the Supreme Court with the extra money.

Additionally, the fear of transaction fees caused me to generally try to avoid trading too much, which I think is a mistake that many other players made. It was common to see people frequently buying and selling shares back around the same price, even though they were just losing money on transaction fees.

As an example of poor strategy, Johnny (the third place finisher) sold 2000 shares of “Trump Indicted Again?” at 99.3% just 70 minutes before it resolved, incurring a loss of $16.7 for absolutely no reason. If he’d just waited a bit and held to resolution, he would have been 16.7 richer with no effort.

As another example, on the final day of the competition, PPPP (tenth place finisher) sold 219 shares in “Trump the Favorite in Summer 2023?”, which was trading at 93.31% at the time, and bought “Send ATACMS to Ukraine?”, which was trading at 8.25%. Obviously, the latter had a better price, and hence higher return in a vacuum (93.31% is equivalent to 6.69% for NO, and 8.25 > 6.69). However, thanks to transaction fees, this was actually a bad trade. PPPP ended up with 0.462845019 in cash and 217.995331618 ATACMS shares. Since this was just 10 hours before the end of the competition, there was no real risk and all shares were effectively worth $1, which means that PPPP effectively turned their original $219 into $218.458176637 by doing this, even though the price on the second market was better and would have made them more money in the absence of transaction fees.

Thanks to the heavy transaction fees, every bet you make should either

- 1) be a bet that you plan to hold until resolution

- 2) a market where you expect imminent huge swings in the market price and are confident you can sell out at a profit

I recently discovered a comment by Johnny from the beginning of the contest where he talked about maintaining a spreadsheet with his “subjective probabilities” for each market, and then buying the ones with the biggest discrepancy from the market prices. I think this might be a trap though, because unless the discrepancy is large, it encourages you to trade back and forth and lose money on transaction fees.

The other problem with the strategy described in Johnny’s comment is that it completely ignored opportunity costs.

7. Opportunity costs are critical

Here’s a puzzle. Consider the “Oil at $100/Barrel During Winter?” market, which asks

This market will settle YES if oil is priced at at least $100/barrel for the months of November 2022-February 2023. Prices are taken from the following link, averaged over the four months.

Imagine it is 11:22am on January 26th. The market is currently trading at 11.3%. You already have three out of the four months of oil prices that are going into the final average, and oil prices have been consistently low during the winter, making it effectively impossible for the average to hit $100. If you buy NO shares now, you’ll get an effectively risk-free return of ~10% in a month. Should you do it?

This was the situation facing Henry A Long (20th place finisher) when he bought $800 of NO and then left a comment on the market asking why the price was so high and why everyone else was seemingly sleeping on the market.

The problem is that you also have to consider the opportunity costs of betting. You have a limited amount of money to bet, the $1000 you start with plus however much you managed to gain or lose from earlier bets. Any money you bet on one market is money you can’t bet on another market. So what other markets could Henry have bet on?

At the time, “COVID Peak of over 300,000 by End of Winter?” and “Mask Mandate in Any State by End of Winter?” were trading at 14.3% and 12.6% respectively, and those markets were effectively risk-free as well.

Even better, those markets were set to close at midnight on February 28th, while the oil market wasn’t set to close until midnight on March 1st. This means that you could take any winnings from the Feb 28th markets and immediately plow them back into the oil market for a tiny bit of extra return. It would probably have been down to like 1% by then, but every little bit helps. (Of course, this turned out to be impossible because the Salem Center inexplicably took several days to resolve all of these markets, but noone could have known that at the time.)

What else was there? Also resolving on Feb 28th were “Will Russia Control Bakhmut?” at 34.9% and “China Reaches 100,000 Covid Cases by Winter?” at 46.6%. Those markets still had a lot of uncertainty and risk, but if you had a confident opinion on them, you could have made much more money (assuming you were right) then the risk-free 14.3% on offer, which in turn was better than the 11.3% available in the oil market.

Long-termism considered harmful

The end result of this is that it takes an absolutely massive mispricing in a long term market to justify actually betting on it, because the profit has to come on top of all the profit you could have made by betting in shorter term markets instead.

Therefore, throughout the contest, I almost exclusively focused on the markets that would be resolving soonest, sometimes betting on the markets that would resolve second-soonest, but not much more. A convenient side effect of this is that it greatly narrows the pool of markets you have to pay attention to and devote mental energy to. At the peak, Salem had over 30 markets open, many of which were useless long term markets that would be impossible to ever profit from, and being able to focus on a small subset of those allowed for applying more careful strategy and analysis.

Notably, Johnny did not do this. Throughout the contest, he had a significant amount of money invested in long-term markets that would only resolve at the very end of the contest. Even worse, a lot of the long-term markets that were available at the start of the contest were massively overpriced the entire time due to the rush of early players who didn’t understand opportunity costs either (for example, “Chinese Military Action against Taiwan?” was already down to 13% all the way back in December, despite not resolving until the very end of the contest.)

To be fair, when you have a large stash of money, the calculus changes somewhat because there are diminishing returns to betting on any one market, so it makes sense to spread things out a bit more, and Johnny was in the lead for most of the contest and had the most money. However, even taking into account his larger bankroll, I suspect that he was massively overweight on the long-term markets, especially since markets like Taiwan offered worse rates than the short term markets even if you completely ignored resolution time.

8. There are invisible opportunity costs, too

Up until January, I assumed that the optimal strategy was to keep your entire bankroll invested at all times. After all, money you have invested will grow over time (assuming you’re right about the outcome), and there were often some effectively risk-free markets to offer a baseline level of “interest rate” as well.

You can clearly see the visible opportunity costs of betting on one market, just by looking at the prices of any comparable markets that resolve at the same time (or earlier). What I didn’t realize until later is that there are invisible opportunity costs to betting as well.

When you bet, your money is effectively locked in until the market resolves. You can sell shares early, but doing so incurs transaction fees, and it takes an especially large profit opportunity to overcome the losses you would take by selling out early to free up money.

What I didn’t appreciate at first is that even if there are no good profit opportunities now (and hence no obvious opportunity costs), a new profit opportunity could appear out of nowhere at any moment. There are several possible causes:

- 1) New news comes out that greatly shifts a market’s price. Even if you aren’t the first person to discover the news, you can still make an easy profit by piling on top before the market resolves.

- 2) Occasionally, people will just make really dumb bets, and you can profit a lot by being the first to trade against them.

- 3) Occasionally, the Salem Center will add new markets. This wasn’t common, and I never saw much of a profit opportunity in them, but it’s worth noting for completeness.

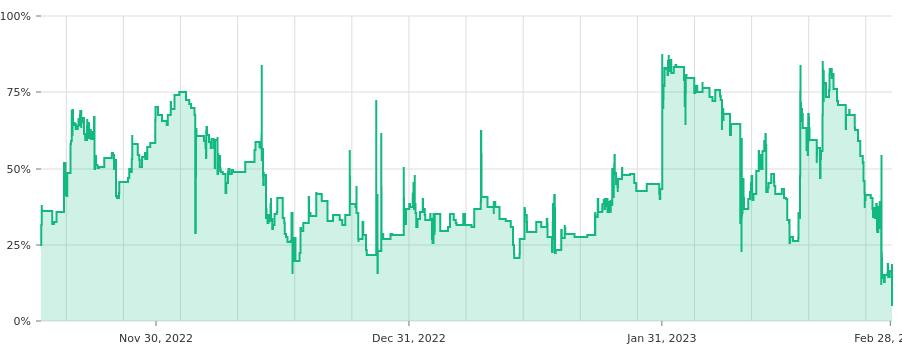

These opportunity costs are unknown and random and not something you can really put a number on, but they are important. In the second half of the competition, I always kept a lot of money uninvested to be ready for such opportunities, and only invested all my money when a market was about to resolve.

9. Predicting the actions of other players is also important

So you’ve managed to predict the outcomes of the markets and when they will resolve, and you’ve figured out the transaction costs and optimal bet allocation. Are you set?

In addition to all that, you also have to predict the actions of other players, because they can move the market prices around with their own bets. I say this not because this is something I ever managed to do (far from it), but because if you did manage it, it would be incredibly useful. Someone who is sufficiently good at predicting the actions of other players could probably win the contest just from that, without even knowing anything else. But of course, predicting what other players will do is easier said than done.

To illustrate the difficulty, here is a pair of examples that where I made opposite mistakes. In the first case, I overestimated someone’s willingness to sell, and in the second case, I underestimated their willingness to sell.

Scenario A: Connor and China GDP

On January 16th, the “China GDP Growth 4% or More in 2022?” market suddenly tanked (from 61% to 20%), driven by Iraklis Tsatsoulis, who found a news article where China announced GDP growth of 3%. That night, I noticed the drop and sold my YES shares and bought some NO shares (20->16%).

The following evening (Jan 17, 5:42pm), Connor Pitts (sixth place finisher) sold some of his YES shares, from 11->7%. I figured that 7% was too low, because the market apparently wouldn’t be resolving until June 30th, and wanted out.

However, I got greedy, and didn’t want to pay the transaction costs from quick-selling at 7%. Just by eyeballing the bet history, I could tell that Connor likely still had a large amount of unsold YES shares that he might want to unload, and I figured that putting down a YES limit at 7% would be a win-win situation. I would be able to sell my NO shares at 7% with no transaction fee, and Connor would be able to sell his remaining YES shares at 7% with no transaction fee. He had already sold some shares at 7%, and a 7% limit would be a strictly better deal for him than what he had already sold at, because it would be a real 7% with no transaction fees on top.

Therefore, I put up a 7% YES limit and then left a comment as well to call Connor’s attention to it. However, for some reason, he never took me up on it, either because he’d already gone to bed or because he had decided that he’d sold enough shares for the time being. Instead, the market price went back up as all the other people who’d bought NO shares during the spike started cashing out. I ended up having to quick-sell at 11% the following evening, and thus got less money than if I had immediately sold at 7%.

Scenario B: Johnny and the Debt Ceiling

In the early hours of June 2nd, Johnny suddenly bought massive amounts of NO shares in the “US Debt Limit Raised?” market, from 4% all the way down to 1.9%. Since the market wouldn’t resolve until the end of the contest nearly two months later, this was clearly a mistake. (It seems that Johnny misinterpreted the resolution criteria to imply that it would be resolving imminently.)

By the time I noticed this, Zubby (first place finisher) had bought $30 YES, and Johnny responded with another $1500 of NO. I was happy to see this because by then, Johnny was my only real competition, and this mistake meant that either his money would be locked up until the end of the contest, or he would sell early and take a hit from transaction fees.

However, the important question was whether to try to punish his mistake by buying YES shares myself, like Zubby had. Even though the market was guaranteed to resolve NO in two months, if I bought YES shares and then Johnny sold a lot and pushed up the market price, I could flip my YES shares for a profit. Even more significantly, any profits in this market would count double for me, because Johnny was my only competition, and thus any additional losses inflicted on Johnny were effectively a profit for me and vice versa.

Unfortunately, I greatly underestimated Johnny’s willingness to sell. I guessed that he would maybe sell from 2% up to 3%, and that the market wouldn’t move enough to make a profit worth the effort. If he had been me, who was pathologically afraid of incurring transaction fees, perhaps Johnny would have stubbornly held until the end of the contest. However, Johnny was Johnny, and he ended up selling all the way up to 5%, netting a handsome profit for Zubby. (The debt limit market later peaked all the way up at 10.8%, not counting Greg’s folly, due to other people selling out later.)

Of course, in some circumstances the actions of other players are predictable, but only due to structural factors that make the patterns impossible to exploit, such as the resolution rush.

10. There is a rush after market resolution

Whenever a market resolves, especially if multiple markets resolve at the same time, you could safely bet that there would be a surge of new market movements as people reinvested their winnings. In particular, I noticed that Mark (eighth place finisher) kept all his money invested all the time (unlike most other top players) and thus would predictably rush to make new bets whenever a market he was in resolved. It wasn’t just Mark though, there were a lot of low ranked players who would also quickly reinvest their winnings.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to predict which markets these people would bet on and which outcome they would bet on, and thus difficult to actually take advantage of this predictable phenomenon. Another difficulty is that the whole reason this phenomenon happens is due to capital constraints, and those same capital constraints would typically make it impossible to exploit for other people, who would likely have their money locked up in the same markets. The only way to actually take advantage of it is to be the first after resolution. Speaking of which, here’s another anecdote:

The Trump Twitter Misplay

On May 31st, there were three different risk-free markets set to close at the end of the month, “Newsom to Run for President by Summer?”, “Will Russia Control Kherson on 5/31/23?”, and “Will Russia Control Kramatorsk on 5/31/23?”.

Near the end of the month, I had invested almost all my remaining money in these markets, to earn a bit of extra return. I only left $200 in cash, and then invested the final $200 on the night of the 31st (for a 2.5% return on Newsom, which was the highest of the three).

Following the end of May, I didn’t have any big plans or ideas for what to do next, but I was planning to put down $500 NO on Trump Twitter, which was at 42.5% at the time. I got greedy and thought that I could earn the extra 2.5% on Newsom and be the first person in on Trump Twitter following the resolution.

The three markets were set to close at midnight, but they don’t resolve automatically. Instead, they have to be manually resolved by someone at Salem, and it is difficult to predict exactly when that will happen, although it usually happens pretty fast (the end of February fiasco notwithstanding).

In this case, Newsom and Kherson resolved at 5:39am and 5:40am respectively, while Kramatorsk didn’t resolve until 7:39am on June 2nd. I can’t imagine why that would happen, since whoever at Salem was doing the resolving would presumably want to resolve all three at the same time, but there were similar, but much smaller disparties in many other market resolutions.

I tend to have trouble sleeping and wake up briefly during the night a lot, and figured that I could check my phone for the resolution email whenever I woke up during the night, so that regardless of when it resolved, I’d be likely to see it early. As it turns out, I woke up (among other times) at 4:08am and couldn’t fall asleep again, and only went back to bed again at 5:31, and then woke up again at 5:37 (but took a long time to actually get up). Since the markets resolved at 5:39am, I managed to just miss the resolution during the one time I was asleep, and by the time I was able to buy my Trump Twitter shares, it was already down to 39.2%. Oh well, there was no way to know what would happen in advance, and the amounts involved were pretty trivial. It was still pretty frustrating though.

On the morning of July 27th, I actually did happen to be the first to wake up and see the market resolution (Q2 GDP), but I didn’t do anything because I figured (correctly as it turned out) that bets on the near-risk-free markets were pointless at that point because everything would come down to the Trump Indictment market and nothing else mattered. I did end up putting 4000 down on the near-risk-free markets later that morning anyway, after other people had woken up and bought them down, but it ultimately didn’t matter.

11. Ranking changes can be paradoxical

In late January, out of curiosity, I calculated what the rankings would be under all possible outcomes for the upcoming Q4 GDP >=1% and Biden Approval >=42% markets (assuming that no further bets happened before resolution). Strangely, I discovered that while I was currently in 8th place, under all four possible scenarios, I would end up in 9th place, a result I dubbed “the paradox”.

It’s not hard to see why this could happen, but it is completely counter-intuitive, and I would have never thought of it before I happened to encounter it in person. This scenario can happen if two people below you have large opposite positions in a market.

For example, if a market is currently at 50%, and A holds $51 in cash while B holds 100 NO shares and C holds 100 YES shares, then A is in first place at current market prices, but no matter how the market resolves, either B or C will take first place. In this case, either Josiah Neeley or Krum-Dawg Millionaire (13th place finisher) would jump past me depending on the outcome of the Biden Approval market.

On the bright side, the same paradox can also happen in reverse if two people above you hold large anti-correlated positions. In early April, I noticed that David (fourth place finisher) and Mark, the two people just ahead of me in the rankings at the time, had opposite positions in the Chicago Mayor market. David had a huge YES bet, while I had a small YES bet and Mark had a medium NO bet, and thus no matter which way the market went, I would either finally reach 5th place or at least gain a lot of ground towards 5th.

12. You don’t have to outrun the bear

When you’re hidden among the teeming masses and the contest is young, trying to maximize your score is basically the same thing as maximizing your eventual rank. However, something funny happens when you reach the rarified top ranks and the end of the contest approaches. At the top levels, people tend to be farther apart, so you only have one or two people you’re in real competition with at any given time, and the correlation between your portfolios becomes just as important as the expected return.

In my case, the final five months of the competition was a story of increasingly competing with just one person at a time, and in many cases, jumping ahead of them thanks to their losses more than my own gains.

Rivals

At the start of March, I was in 7th place, but effectively in 6th place (Ben was just ahead of me in 6th, but he’d been inactive since early December and I knew I could pass him without trying - Ben eventually finished in 7th), and I was desperate to make it into the top 5. Ahead of me, my competition was Connor, David, and Mark in 3rd, 4th, and 5th place respectively. Zubby and Johnny were in 1st and 2nd, but they were so far ahead of me that I knew I had no chance of catching up with them. Meanwhile, 8th and below were fairly far behind me, so I didn’t have much to worry about behind me unless I lost a lot of money.

Therefore, in March and early April, I considered Connor, David, and Mark my “rivals” and cursed whenever they made a profit, as it put 5th place that much further out of my reach. Meanwhile, I didn’t mind at all when Zubby and Johnny rapidly jumped on every profit opportunity, since I had no chance of passing them anyway and it at least meant that Connor, David, and Mark weren’t getting that profit.

On April 4th, the night of the Chicago Mayor election, David self-immolated (due to his massive failed bet on Vallas) so I reached 5th place by default (though I did make a decent profit on the election through my own efforts, too). Furthermore, Connor stopped playing following the election, and once that became clear, I knew I would eventually pass him without much effort. This left Mark in 3rd place as my sole rival.

I even temporarily changed my name on Salem to “I’m coming for you, Mark”. On May 15th, following DeSantis’s candidacy announcement, I finally passed Mark, and thus set my sights on second place, Johnny, although he was far out of reach, and his lead soon got even more impossibly large following the debt ceiling debacle, where I took significant losses and Johnny had huge gains.

I knew it would take multiple miracles in a row to overtake Johnny and didn’t have any real hope, but I kept playing anyway, so that I’d be better positioned just in case the stars aligned.

Fortunately, the stars did align, and at the end of June, following the Supreme Court announcements, I made a huge profit and closed most of the gap, so that I could plausibly overtake Johnny if I just got lucky a few more times. Meanwhile, Mark self-immolated. I was already far ahead of Mark anyway, but it meant that I was even more secure in 3rd place, as that left just the inactive Connor behind me. As long as I bet conservatively enough to leave more cash than Connor in the event of a loss, I was basically guaranteed to at least get third place, so the only question left was whether I would somehow manage to overtake Johnny and get second instead.

For the final month of the contest, I played with a single-minded devotion towards overtaking Johnny, treating his losses as interchangeable with my profits, and vice versa. My strategy primarily revolved around looking at the few places where he had large bets I disagreed with, and betting the other way and hoping that the market would resolve in my favor rather than his (and that he wouldn’t sell his shares first).

In the particular case of the Q2 GDP market, I put a lot of effort into trying to discourage Johnny from selling his NO shares, hoping he would hold them to zero (as he ended up doing). And while I temporarily slipped ahead of him thanks to my win on GDP, what ultimately sealed his fate was his massive losses on the Trump Indictment market, which I had absolutely no control over. (I suspect that Johnny bet so heavily on the indictment market because he was in turn trying to overtake Zubby and reach first place.)

13. Always read the fine print of the resolution criteria

Two of the markets on Salem ended up revolving around a very different question than the one suggested by the title of the market. Ironically, I made huge gains in the first one, and took heavy losses in the second.

China Reaches 100,000 Covid Cases by Winter?

The first of these was titled “China Reaches 100,000 Covid Cases by Winter?”. The resolution criteria read as follows:

This market resolves as YES if China reports a 7-day rolling average of at least 100,000 covid-19 cases at any point between the opening of the market and February 28, 2023. Source for settling the market will be Our World in Data at the link below.

https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer

Should that source be unavailable, a suitable alternative will be found.

In early December, China ended its “zero COVID” policies and instead let COVID spread unchecked through the population. However, they also revised their testing criteria, and continued to report very low case numbers, even as COVID ravaged the country.

On December 17th, Salem posted an update to confirm that the market would resolve based on reported COVID numbers, rather than whether China actually had a surge of COVID cases.

This market was never meant to estimate the true number of cases in China, but was always to be based on government reports. Thus, any alternative source to Our World in Data will have to rely on official numbers to be used. If at some point China stops reporting data completely, this market will resolve as NO as long as there was never 100,000 cases reported for any 7-day rolling average.

By early January, the December wave was over and China was still reporting low case numbers, so the market seemed pretty safe. The only risk was that the Salem Center would somehow be persuaded by the brigaders to resolve the market YES, even though by all rights it should be NO. Oh, did I mention the brigading?

Back in November, a player named Andy Martin had been betting heavily YES, hoping that the November wave (before China lifted Zero Covid) would break 100k. As it turns out, Andy Martin was also active on Manifold Markets (the sister site that the Salem contest was forked from) and created a prediction market on Manifold with the same title and with resolution criteria saying that it would resolve to match the resolution of the corresponding market in the Salem contest.

A lot of players on Manifold bet on Andy’s market based on the title, assuming it was an obvious YES, and got furious when it became clear that the resolution of the Salem market (and by extension the Manifold market) would be based on reported case numbers rather than actual cases.

One of these people, Patrick Delaney, went so far as to sign up for the Salem contest for the sole purpose of trying to persuade the Salem Center to resolve the market YES so he would win imaginary money on the Manifold site. He spent the next two months endlessly commenting on the Salem China COVID market, arguing, insulting, wheedling, and throwing out any argument he thought might stick. He was quite persistent at it, and the China COVID market ended with 340 comments, far more than any other market on Salem. (To be fair, many of those came from Iraklis and other legitimate players on Salem as well.)

In mid January, China stopped reporting COVID cases entirely, causing me to get more worried about the market again. One line of argument from the YES side was that this meant that the source was “unavailable” as per the resolution criteria and thus “a suitable alternative” should be used. In my opinion, this was nonsense since the listed source (Our World In Data) was still up and still showing numbers, it just showed zeros for recent days, but there was a chance Salem might be persuaded anyway.

Then at the end of January, the market suddenly got completely upended again. Our World in Data (the source used for resolution) in turn sourced its data from a repository maintained by John Hopkins. On February 1st, they announced on Github that they would be working to integrate the WHO data (which had vastly higher case counts) into their repository, apparently retroactively.

At that point, I assumed I was certain to lose and turned off all notifications and stopped checking Salem entirely for the month of February. As it turned out, the market continued to swing wildly up and down over the course of February, before ultimately resolving NO. It’s hard to tell exactly what happened, but as far as I can tell, what happened is this:

- John Hopkins decides that they are unable to integrate the WHO case data after all because it doesn’t break out Hong Kong and Taiwan from the mainland.

- Our World in Data announces that they’ll stop using John Hopkins and switch to using the WHO data directly, and that this change will be retroactive.

- However, the OWID switch to WHO data is scheduled for March 8th, after the end of the market.

- At the end of February, the graph on the OWID site still showed the John Hopkins numbers, but the spreadsheet download link already showed the WHO data, and it was unclear which would be used for resolution.

In any case, this market was an utter disaster, and the outcome ended up being a coin-flip completely divorced from any sort of predictable reality.

Incidentally, Andy Martin ended up resolving the linked Manifold market as “N/A” rather than “NO” as he felt that the NO resolution on Salem was unfair.

US Debt Limit Raised?

The other disaster market was simply titled “US Debt Limit Raised?”. The resolution criteria read

This market will settle as YES if Congresses[sic] passes a bill that the president signs that raises the US debt limit by July 31, 2023. If the president vetoes the bill, and his veto is overturned on such a bill, the market will still settle YES.

On January 26th, Zubby commented, asking “Would a bill suspending the debt limit count? Does minting the coin count?”, to which the Salem Center responded “No”. However, I didn’t appreciate the significance of this comment at the time and unfortunately forgot about it.

Throughout March, April, and May, the market price slowly rose, reaching a peak of 93% on May 28th (which is unfortunately when I bought in). Then overnight, it suddenly tanked.

It turns out my mistake was in naively assuming that the market was asking a meaningful question (as well as relying on the belief implied by the market price that everyone else was assuming the same thing.) Throughout the spring, the one question on everyone’s minds in the US was whether congressional Republicans would reach a deal with Democrats to avert the debt ceiling crisis, and it was natural to assume that that was what the market was trying to measure.

However, this turned out to not be the case. Despite congress reaching a debt ceiling deal in the end, the market resolved NO on a stupid technicality - the deal suspended the debt ceiling rather than raising it. Instead of trying to measure the actually important question that was on everyone’s minds, the market secretly revolved around a stupid question that noone cared about, “which color will the resulting bill be painted?”.

I suppose the best that can be said is that I was evidently in good company misinterpreting the market. Most of the debt ceiling deals over the last decade involved suspending the debt ceiling rather than raising it, so just on the basis of historical data, the YES probability should have been really low. The fact that it got up to 93% implies that everyone else also misinterpreted the market and assumed it was about the actually interesting question, not a stupid gotcha.

In fact, Richard Hanania himself, the founder of the contest, was fooled by this market as well. On February 15th, he wrote

The debt limit standoff is one of the main issues in Washington, with both sides seemingly unwilling to compromise. The market seems optimistic about finding a solution, with 77% thinking that the debt ceiling will be raised by the end of July.

Obviously, that is not the way one would write if one understood that the market was actually supposed to predict a dumb gotcha rather than “the main issues in Washington”.

14. The markets started highly inefficient, but got a lot more efficient towards the end

Every once in a while, someone would make a really large dumb bet, and the first person who happened to see it (usually Johnny) could profit enormously by trading against it.

By pure chance, I decided to check Salem while on Christmas vacation, at 6:40am on December 28th. Coincidentally, at 6:08am, Dylan Levi King (a high ranked player at the time) had bought China COVID from 23.0% up to 61.3%. Johnny jumped in at 6:15am, seven minutes later, and bought it back down to 53.9%, but that meant it was still pretty high when I happened to see it half an hour later, and I was still able to make some profit buying it myself.

In early January, I tried to make lightning strike twice by placing limit orders on many markets at way above or below the market price, in hopes of profiting if someone like Dylan Levi King went crazy again. Unfortunately, this proved to mostly be ineffective or counter productive (as you lose money if a market suddenly changes for legitimate reasons), so I stopped doing it.

Instead, I checked Salem several times a day, particularly in the morning and evening, in the hopes of happening to be the first person to see a major market movement, and continued doing the same after I returned in March, though my efforts yielded little.

On March 28th, at 10:22:49, someone named Alec Cenci suddenly tanked “Will Donald Trump Be Indicted for a Crime by July 2023?” from 72.3% down to 28.5%. At 10:26:57, just four minutes later, Zubby bought it back up. Zubby’s reaction was so fast that I thought he might have had a bot, but he said that he just got lucky and happened to be on at the right time.

Throughout March, I noticed that Zubby tended to be the first to react to major market movements, and Johnny always jumped in afterward, and hence got the worse prices after Zubby had already taken most of the profit. I even mentally nicknamed him “Johnny come lately”. However, this pattern reversed in April, with Johnny being all over the markets and Zubby nowhere in sight.

The bot wars

On March 30th, Johnny responded to my question about Zubby’s four minute trade saying that he actually did have a bot to notify him of sudden market movements (given the advantage of his bot, it’s unclear why he was still slower than Zubby in March).

I decided that I needed to create a bot of my own so I wouldn’t be fighting with one hand tied behind my back. However, I procrastinated on it for three weeks and only finished the bot in late April, and my bot didn’t work very well anyway.

I set up a Python script on my desktop to fetch the market data from Salem every 15 seconds, and then email me via the Gmail API whenever a market moved more than 7% in a 15 minute period. Unfortunately, I never found a way to get the Gmail app on my phone to notify me, so it was hard to actually see the emails. In fact, I never managed to get Gmail to even mark the bot emails as important, even when I specifically created a Gmail filter to mark them as important. Additionally, for some bizarre reason, Google forcibly expires app tokens every 7 days, forcing you to manually delete the token and reauthenticate (which involves clicking through the scary warnings in the browser), with no way around this, and occasionally I would forget to regenerate the token, leaving the bot temporarily unable to send emails.

I was originally hoping to have my bot send an SMS message, which I would definitely be able to notice regardless of the time of day or location, but unfortunately, I never managed to find an SMS api that actually worked. Twilio is basically the only game in town, and for some reason, they immediately blocked my account on signup with no explanation. It sounds like nowadays only businesses can use Twilio, but they aren’t nice enough to actually tell you this. I also tried every other SMS api provider I could find (such as Vonage), but none of them worked.

The end result was that while I did have a bot to notify me of market movements, it relied on me happening to be on the computer at the time and happening to notice the new email in Gmail, so it would only occasionally even be possible for me to see the email, and even under ideal circumstances, it would take me minutes to notice it.

On April 19th, someone bought the Russia Donbas market from 15% up to 29%, and it stayed that way for ten hours before Johnny bought it. Once I finally got my bot working, there were one or two cases when I managed small wins like that, and it wasn’t clear to me why. I theorized that Johnny had his bot set to a higher threshold and just wouldn’t notice relatively small market spikes like that.

The Josiah Neeley incident

Unfortunately, Johnny was still the fastest and most consistent when it actually mattered.

On April 27th, at 9:21:53, Josiah Neeley, then one of the high-ranked players, went crazy and put all his money on YES on “Newsom to Run for President by Summer?”, spiking it from 7.53% to 67.34%. (Josiah had just lost half his money gambling on the GDP market, and presumably decided that he had no chance playing normally and might as well YOLO it all on an extreme longshot bet. Incidentally, Johnny was also the one to trade against Josiah’s wild GDP bets the previous night, but I didn’t begrudge him that, because the GDP market was legitimately risky, and I would have stayed away out of uncertainty even if I had been the first to see those trades.)

At 9:34:55, thirteen minutes later, Johnny jumped in and bought it back down, making a massive profit, likely the biggest of the whole contest. This was shortly after I had finally got my bot working, and I was absolutely furious when I found out. By all rights, that should have been my windfall. If only I had managed to find a working SMS provider, I could have easily gotten the phone notification and bought the spike in under 13 minutes. It especially stung because for the last month, I’d been the main one participating in the Newsom market. The GDP market, I didn’t mind, but Newsom was my domain.

Zubby strikes back

On May 16th, at 12:19:41, a nobody suddenly bought “Biden the Favorite in Summer 2023?” from 85.6% down to 62.9%. At 12:20:05, just 24 seconds later, Zubby bought it back up, and then at 12:21:29, Johnny Come Lately stepped in to pick up the dregs, presumably greatly disappointed.

Surprised at the quick reactions, I commented on the market, and they responded:

Johnny: Well I have a script that polls for market changes once a minute and happened to be at my computer anyway. Still I frankly felt quite good about how quick I was. Until I looked at the actual seconds via the API: My 107 second reaction time got easily outclassed by zubby’s 24 seconds.

Zubby: A couple months ago I saw J10 aka The Goat clearly had some sort of monitor running and I decided I needed to do the same. I was on a golf course when Josiah Neeley decided to rage quit in the Newsom market, which is why I was extra mad!

This was doubly unfortunate news because it showed that both a) Zubby had a bot too and b) Zubby and Johnny were fast enough that I wouldn’t be able to profit off any spikes that came up even if the stars aligned and I happened to see the bot email at the right time. Previously, Johnny had typically been taking 7-15 minutes to jump on these things, which was plenty of time if I got lucky with the bot email, but at only one minute, I would have no chance even if I did get the bot email.

A new hope

On May 28th, at 15:56:46, Dylan Levi King tanked the Trump Indictment market (48.2%->24.7%). This time I happened to be on the computer at the time and happened to be the first to see the email, but I quickly checked Google to see if there were any news stories that would justify the drop before I invested. While I was still researching it, Zubby bought it back up at 15:58:52. In retrospect, I should have just speculatively put a small amount in before researching it.

On June 23rd at 21:08:42, a nobody (Guangyu Song) bought up Russia-Ukraine Ceasefire 12.3->62.5%. Amazingly, this time I somehow managed to beat Johnny to the punch and bought it back down with a speculative $100 NO at 21:11:27 (remembering the Zubby incident) followed by $1000 NO at 21:13:20 once I’d checked the news, and then another $400 NO at 21:22:37 because for some reason, Johnny still hadn’t jumped in.

For some bizarre reason, Johnny didn’t show up until 03:24:55, over six hours later. Presumably, he just didn’t get the bot notification for whatever reason. Previously I’d thought that it was due to his bot threshold being too high, but this jump was big enough to trigger any plausible threshold. Maybe Johnny was just asleep at the time. On the other hand, Johnny had a limit order which triggered in this case, so he got part of the profit without being awake.

Johnny was still massively ahead of me, but this incident did at least reduce the gap a bit and gave me the hope that perhaps I could reap similar windfalls in the future. Sadly, it was never repeated, and for the rest of the contest, Johnny and Zubby were very fast at grabbing these things.

Salem Plus

In January and March, I checked Salem several times a day, but this was suboptimal because the website takes a long time to load and the UI makes it hard to see relevant changes. In early June, I wrote a very barebones HTML + JS site that I dubbed Salem Plus.

Salem Plus loads the market data from the main Salem site (using the API), but displays it in a much more convenient view. Specifically, it shows the ten most recent bets for each market in a flat single page view, with the markets sorted top to bottom in order of the most recent bet. This allows you to quickly see all recent activity, something that would require painstakingly clicking through to the bet history for every individual market on the real Salem website. Additionally, Salem Plus displays the exact market prices rather than rounding to the nearest percent like Salem does, and it probably loads faster as well.

This wasn’t the original purpose of Salem Plus. My original plan was to take all the Python scripts I had built and rewrite them in Javascript and embed them in a custom website so I could use them while on vacation when I didn’t have access to my normal computer. However, I never got around to actually doing that. I just wrote a very barebones read-only page to display market data and didn’t bother to do any of the rest.

Even this proof of concept though turned out to be really useful, as I was able to check it periodically to keep abreast of activity in the markets. Initially, I would just check it several times a day, but near the end of the contest, I started checking it much more frequently, refreshing it every 10-40 minutes throughout the day, depending on how bored I was at the time. I’d pretty much given up on my email bot, but figured that if I checked Salem Plus frequently enough, I would still have good odds at seeing any opportunities that came up anyway.

The final week

On July 24th, Monday of the final week of the competition, all eyes were on the “Third Trump Indictment?” market, the only market left with any real uncertainty. At 14:19:57, PPPP bought it up (54.2->63.8%) and Johnny and Zubby immediately bought it back down at 14:21:35 and 14:21:41 respectively, less than two minutes later. (I was sitting that market out due to uncertainty and wouldn’t have bet against PPPP even if I had been the fastest.) However, the most impressive part was yet to come.

At 14:53:06, DfromBham (19th place finisher) suddenly bought Trump Indictment up from 54.3% to 70.9%. Somehow, Zubby bought it back down just 22 seconds later at 14:53:28. I couldn’t believe it and left a comment to ask Zubby how he managed to do it. He responded “Just running a page monitor and was at my computer.”

Inspired by Zubby’s comment, I modified Salem Plus the following morning to refresh every 15 seconds in the background, and left it open in the corner of my computer all the time, hoping that market movements would catch my eye.

Following the resolution of the Trump Indictment market Thursday afternoon, the competition was effectively over, but I knew there was still a slight chance of someone pulling a Josiah Neeley and feeding Johnny enough for him to overtake me, so I kept an eye on the markets just in case, albeit nowhere near as intensely or consistently as I had been doing earlier in the week.

As it turned out, there were two final mini-spikes the following day. One happened overnight (03:58:52), and Johnny got it (04:01:39, less than two minutes later). The other, larger, spike happened in the afternoon, when Greg Simitian, a new player, put his entire starting $1000 on YES on Debt Ceiling.

Greg did this as 100 individual bets of $10 each, from 14:41:53 to 14:42:42, so it’s hard to know which starting point to measure the reaction time from, but in any case, Zubby got it extremely quickly at 14:43:05. Oddly, Zubby only bought it partway back down, so once I got back to the computer and noticed at 14:46:51 (I’d been eating at the time), I put in a bunch of money myself, figuring that if I didn’t, Johnny would. However, Johnny never bothered with the market, even after commenting on it later on. In fact, his very last bet of the contest (prior to the very end) was at 04:02:55 when he bought the first spike. Presumably he just gave up after that, though he did still go to the trouble of investing his excess cash five minutes before the contest ended.

15. Luck is important, too

When the contest was first announced, many people worried that the winner would just be someone who went all in on an unlikely bet and happened to win big. Fortunately, the contest was long enough that that didn’t happen. All the top players were people who were able to consistently win many bets.

That being said, luck was still important. In my case, there were two points (the November Midterms and China COVID) where I had most of my money on a bet that I didn’t think would actually pay off, and in both cases, I fortunately managed to win anyway. In the second case, I thought it would take a miracle for the market to go my way, and even stopped playing and stayed away from Salem entirely for a month while I waited to find out what happened.

Of course, it’s important not to overstate this. The “miracle” took me from 9th place to 7th place, while I finished the contest in second place, so it clearly wasn’t just a matter of getting lucky twice. But I do think that in order to win the contest, you have to have good strategy and put in hard work and also get very lucky as well.

Conclusion

In this part, I covered the main lessons I learned while participating in the Salem prediction market tournament for the last year. In the next part, we’ll go through a detailed chronological account of the tournament, seeing how it unfolded and how my strategy changed over time, and the ups and downs along the way. (Fortunately with a lot more ups than downs!)